Starting in the 15th century, Venice was emerging as a printing hub, when itinerant peddlers known as venditori ambulanti began disseminating pamphlets, ballads, and religious tracts1 across the peninsula. During the Reformation, this grassroots network shaped public opinion, with peddlers navigating Catholic censorship to distribute Protestant and Catholic texts. These early distributors, often undocumented, were central to cultural and religious shifts, making printed ideas mobile.

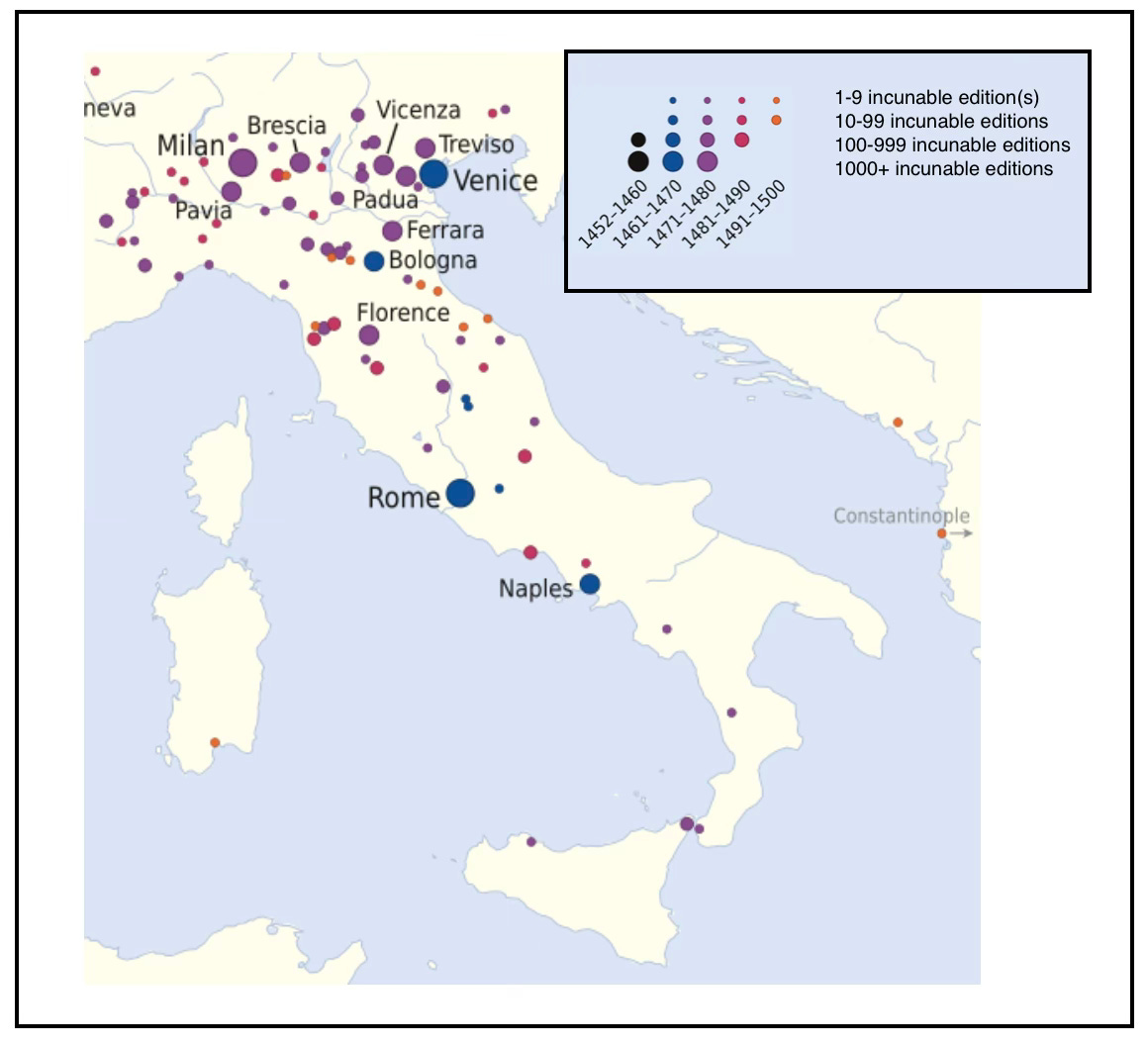

From hubs in Venice, Bologna, Rome and Naples, these printed works radiated outward. Below is a map of early printing towns across Italy. These were places where incunabula2 were produced and then disseminated. The colored dots indicate the decade in which they started to crop up, as well as how many editions were being produced and where.

Yet producing books was only part of the story - getting them into readers’ hands across Europe presented a whole new set of challenges. In an article from The Groiler Club on The Book Peddlers of France, the author states how difficult it was early on in Europe to take possession of books [1]:

Rough terrain slowed down shipments, licensing and copyright laws limited what books could be sold where, and religious and secular disputes over the content of the books further complicated matters.

Nonetheless, according to an article on an exhibition titled Colporteurs – I venditori di stampe e libri e il loro pubblico (Colporteurs - Print and book sellers and their audience) [2], bureaucratic and logsticial hurdles weren’t always detrimental:

The peddler’s trade was often carried out with dignity and professionalism, enabling social ascent, the purchase of a shop, or even a publishing house, and should not be confused with the ever-mobile groups of charlatans, swindlers, or beggars who frequented the same roads and markets.

The brief article goes on to mention how these hawkers spurred the creation of a collective European imaginary. Expanding on this idea, epic printed poems from the late 15th and early 16th century Italy, such as Orlando Innamorato, Orlando Furioso, and Morgante offer a glimpse into that shared imagination. Produced and distributed via early printing presses in Venice and other towns, they spread heroic deeds, via tales of knights, love, and moral struggles within a Christian framework.

This religious backdrop was never meant to be far from the minds of readers - Rome and the Holy See made sure of that. As printing flourished, controlling its content became a priority for authorities, leading to formal mechanisms of censorship.

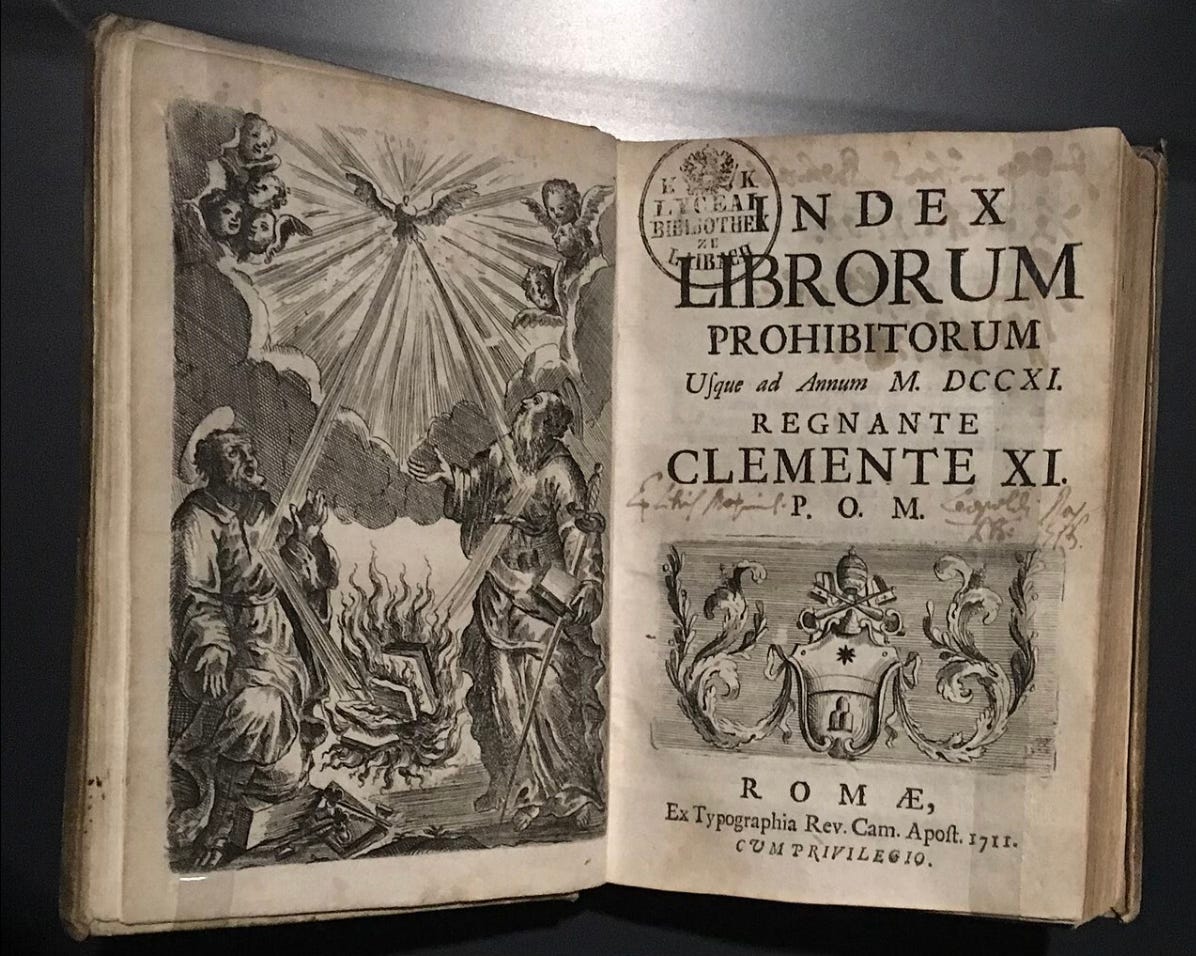

Index of Forbidden Books

The Index Librorum Prohibitorum, or Index of Forbidden Books, was a heretical list of banned books that started in 1560 and lasted four centuries. Perfect candidates for exclusion included theologians challenging papal power, astronomers pushing Copernican ideas, progressive philosophers linked to pantheism, and those who questioned faith with reason. The Index went even further, banning Protestant texts on secular subjects such as botany, medicine, jurisprudence, geography and cosmography.

One of its six regulae, or rules - that was more a consequence than a criterion for banning - was related to ownership. Catholics were forbidden from reading, owning, selling, or distributing listed books under penalty of sin. For the Church, printing was a double-edged sword; on one hand, it allowed for the spread of the holy word but, on the other, its democratic nature made way for all manner of competing and unrelated thought to flourish. This was, after all, the same general period as a split in the Church known as the Protestant Reformation.

Permissions to print

Catholic censors declared a book nihil obstat3 if the publication had no offending declarations, followed by an imprimatur4 from a bishop permitting its publication. To give a real-world idea of what this meant, of the roughly 8,150 editions5 printed in Venice from 1550 to 1599, around 71 new titles per year required a governmental imprimatur [3].

In this case, the use of “governmental” refers to permission from the Republic of Venice, which is different from the Catholic Church’s imprimatur for doctrinal approval. In other words, as an important printing hub, Venice exercised independent control over its presses while occasionally pushing back against the Church’s Index restrictions. At times, this backfired, as wealthy Venetian bookstore owners often had shops across Italy.

With countries - or rather, kingdoms and republics - tightly controlling the printing process within their borders, it led to a market for the clandestine sale and trade of forbidden publications - a job that was carried out by hawkers, including transnationally. One is reminded of the Tesini pedlars from the Italian Alps, active from the 16th to 19th centuries, who distributed affordable prints across Europe on foot.

The demand for hidden texts naturally shifts the focus to how such materials reached their audiences and the distinction between distribution and dissemination. A study that investigates these terms is The Dissemination of European Popular Print: Exploring Comparative Approaches [4]. In it, the authors show the physical transportation of printed materials like books and pamphlets differed from broader cultural processes, including the meanings, social interactions, and multimediality (eg, oral performances, adaptations, and non-commercial exchanges) attributed to them.

The paper also opens up the discussion to the many types of sellers, such as peddler, hawker, chapman, street vendor, and colporteur. In turn, these could further be categorized by wealth, credit, trade practices, or specialization in printed matter versus other goods. So while they weren’t necessarily “charlatans, swindlers, or beggars”, they also weren’t homogeneous either.

Conclusion

No matter the viewpoint, book peddlars benefited the local government via taxes and licenses, allowed low income residents to have an income and supplied literature to people in rural areas, among other things. They were crucial to both the dissemination and distribution of written ideas, and thus popular movements, in addition to helping form cohesive cultural identities.

In an era when Venice’s ruling class curbed open discourse to preserve order, lively public chatter filled streets and squares, where peddlers democratized ideas by spreading printed materials to the masses. Their work fueled Italy’s literary spread, leaving their mark in urban spaces, rural homes and everywhere in between.

Sources

1 - The Book Peddlers of France

2 - Colporteurs – I venditori di stampe e libri e il loro pubblico

3 - The Roman Inquisition and the Venetian Press, 1540-1605 (pdf)

4 - The Dissemination of European Popular Print: Exploring Comparative Approaches (pdf)

5 - The normative role of public opinion in the republican experience of Renaissance Venice (pdf)

concise pamphlets, typically 8-24 pages, used during the Reformation to debate theology or politics, often anonymously to evade censorship

book, pamphlet, or broadside that was printed in the earliest stages of printing in Europe, up to the year 1500

Latin for “nothing hinders”

Latin for “let it be printed”

If adjusted for reprints and unreported publications, with an average print run of 1,000 copies, this totals over eight million books just in Venice