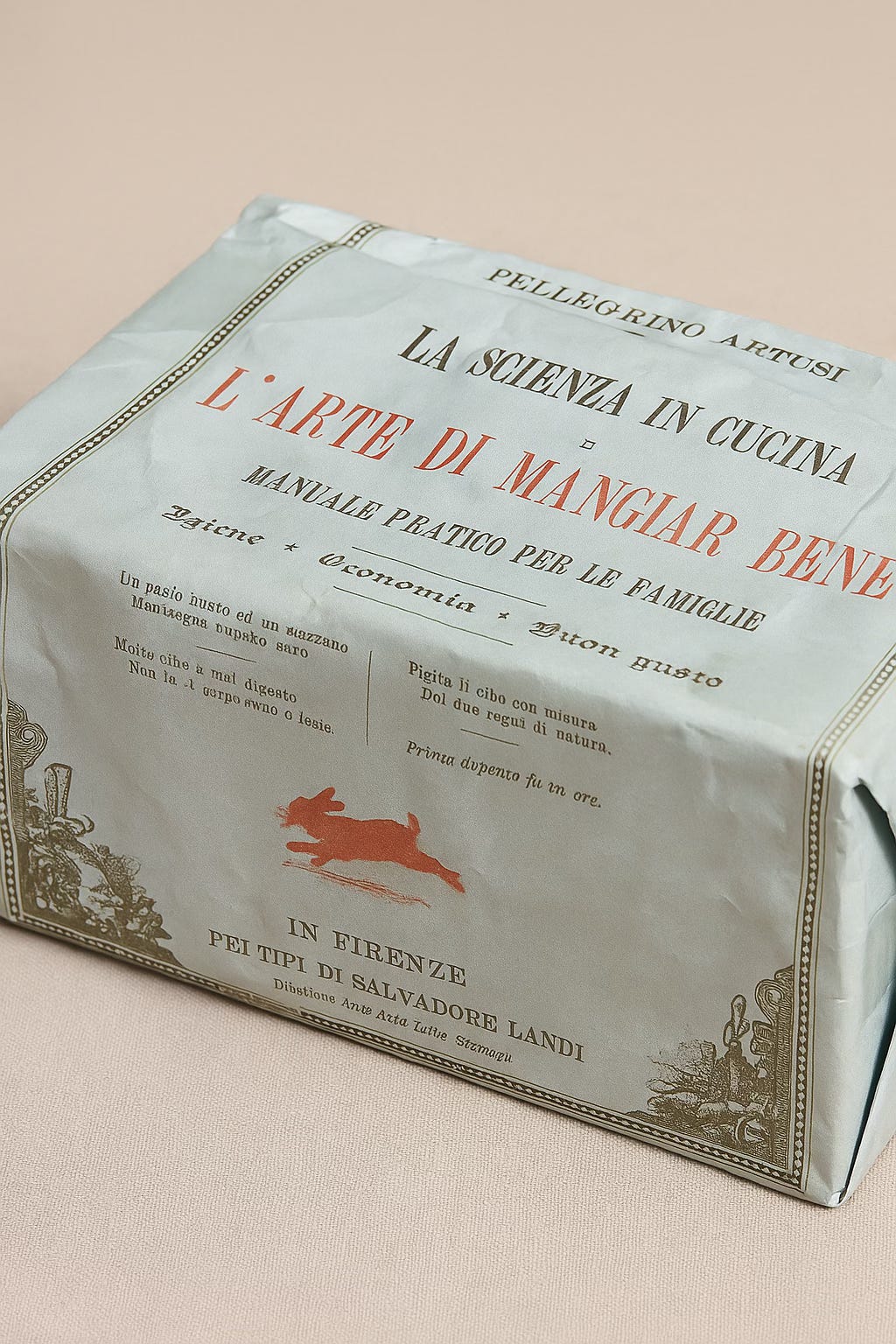

If there’s a single book that defines Italian cooking, it’s La Scienza in Cucina e l’Arte di Mangiar Bene (Science in the kitchen and the art of eating well), by Pellegrino Artusi. Written all the way back in 1891, it originally wasn’t a bestseller. “L’Artusi”, as the book is sometimes referred to, originally consisted of 475 recipes - now 790 - from all over Italy, which required two decades to gather and curate, and selling 52,000 copies while the author was still alive1.

Even though Pellegrino Artusi was from a very well-off background, his book was geared towards middle-class families and everyday housewives. Not only that, it wasn’t the first book of its kind - there were other cookbooks featuring regional cuisine - and he wasn’t even a cook, so we can think of him more like the first food blogger of his time, or perhaps equally, an amateur scientist.

He also pushed back against the dominant haute cuisine, which was the French model of fancy, highbrow cooking. This was not because Italians weren’t sophisticated, but because such cuisine didn’t fit the needs or tastes of Italy’s growing middle class, especially the urban women who were starting to run their own kitchens [2].

This shift in culinary focus occurred in a country still recovering from centuries of economic stagnation. As one study notes [3]:

From the 17th century until the end of the 19th, GDP rose as the population increased. Yet per capita income slowly diminished together with real wages, urbanization, and living standards.

The book’s title is intentional as it aligns with the 19th-century positivist movement that sought to apply scientific principles to all areas of life, even cooking. In fact, Artusi argued that the cookbooks of the era weren’t useful as they didn’t include basic information like dosages. In the preface, however, he describes a less rigid, more playful side to his approach [1]:

The kitchen is a little rascal; it often and willingly drives you to despair, but it also brings pleasure, because when you succeed or overcome a difficulty, you feel satisfaction and sing victory.

If you don’t aspire to become a master chef in some grand court, I don’t believe it’s necessary to be born with a saucepan on your head to succeed. All you need is passion, great attention, and the habit of being precise. Then, always choose the finest quality ingredients, those alone will make you shine.

So what exactly made Artusi’s book special? Well, the breadth and scope of the recipes he gathered, for one, and he did it at a very opportune time in Italian history - in the period during and after the unification of Italy. In other words, he helped populate people’s minds with a novel notion: what it means to be Italian. And it apparently worked, as Italy and its food culture are tied at the hip - or rather, the panza2.

Political unification did not mean cultural or even economic unification. Linguistically, they couldn’t understand each other. But food has long been the great unifier, though it would be wrong to say that his initial editions were truly representative of the peninsula and the isles. Artusi, being from Romagna, favored both northern and central regions including Tuscany and what is now Emilia-Romagna. That said, a later edition in the year of his death, included many more contributions which more fairly represented the newly formed country.

How did he do it? By trying recipes he already knew, collecting others from those around him, and roaming from restaurant to restaurant, bakery to bakery. He took meticulous notes and also any anecdotes that were told to him in the moment, such as the situations and circumstances around which certain foods came to be cooked. Perhaps too many anecdotes, as the book didn’t sell well initially and was said to be boring, with too many irrelevant facts. Some shops would reportedly receive the books for sale but when no one bought them, the shopkeepers used the pages as wrapping paper for items purchased. Not quite like taking a hammer to a David and using the pieces for gravel, but perhaps sacrilegious in its own way.

Some traditional foods weren’t included simply because he personally did not like how they tasted, though others were included despite his distaste for them. People started to send him their recipes, too, once the book caught on. With no children, never married, and only two beloved cats3, he left the rights to his book to his two kitchen helpers who were at his side the whole time.

Artusi worked on his recipes until his final days. In his eighties, he could still see just as well as always, and regularly revised subsequent editions. By age 90, the year he died, he was still correcting recipes. La Scienza’s success surprised and delighted him, keeping him engaged until the very end [4].

Fittingly, given his legacy as the creator of the first true Italian cookbook, his death in March 1911 coincided with Italy’s 50th anniversary, marked by celebrations across the country. On the centennial of Artusi’s death, in 2011, there were many celebrations across the country as well. And that’s not all. Since 1997, his hometown of Forlimpopoli has celebrated the Festa Artusiana, an annual food and entertainment festival in his honor.

Effects

L’Artusi, which has sold over a million copies, and has been translated into ten languages, remains a beloved classic. Its modern success is in part thanks to a version published by Einaudi in 1970 and edited by noted historian and gastronomist Piero Camporesi who once reflected how La Scienza did more for national unification than the 1827 book I promessi sposi (The Betrothed) managed to do. And as the latter is the most widely read novel in Italian and a cornerstone of Italian literature whose use of Florentine Italian helped standardize the national language, that’s no small feat!

The curious reader can peruse the more than 1,800 letters he received from all over Italy, and the world, using the digital archive at Casa Artusi. These were the letters that contained the recipes that helped build the book and the gratitude that grounded the project - a living dialogue between Artusi and a nation finding itself through food.

As famed chef Massimo Bottura said in a 1st edition reprint, “L’Artusi paved the way for us to get to know ourselves and our nation, one spoonful at a time.”

Additional Information

1 - Culinary Luminaries: Pellegrino Artusi | The New School (video, 1h18)

2 - Pellegrino Artusi. L'unità d'Italia in cucina (video, 14m, English subs)

3 - Verso una cucina, lingua ed identità nazionale: uno sguardo storico attraverso La Scienza in Cucina di Pellegrino Artusi (pdf)

Sources

1 - L’Artusi (both first & modern editions, pdf, in Italian)

2 - Pellegrino Artusi - La scienza in cucina e l’arte di unire l’Italia a tavola

3 - The Italian Economy Before Unification, 1300–1861

4 - Artusi, un secolo dopo: il gentiluomo in cucina

5 - Mostra Pellegrino Artusi. Il tempo e le opere

and 200,000 by the time he died

panza is an informal Italian word for belly or gut, often used to evoke appetite & indulgence.