When Isabella II was overthrown in the 1868 Revolution, it brought about a push for economic modernization at a time when Spain was financially strained. A few months later, the Mining Law passed which would open up the country to foreign capital and companies. Very liberal concessions were granted and made in perpetuity, starting a boom in the mining of mercury, copper, lead and iron, which would fuel the industrial revolution already occurring across the UK and Central Europe [1].

The source of all these raw materials was the Iberian Pyrite Belt, running from Setúbal in Portugal to Seville, which is the largest concentration of massive sulfides in the world. Mining in the Huelva province had been occurring since the time of the Phoenicians, continuing through the Roman, Moorish and Christian rule.

The resumption of mining in the 19th century was no coincidence. Advances between 1833 and 1859 enabled the full use of pyrites, as sulfur was found to be exploitable, capable of producing sulfuric acid, and copper was extracted from desulfurized pyrites. These developments were of great use to the electricity, transport, chemical and fertilizer industries [2].

Even before the Mining Law, Spanish engineer Luciano Escobar saw the potential in escavating at the Tharsis mines of Huelva, where any serious activity had been dormant since the Roman times. In the 1850s, he presented a proposal to businessmen from the region but it fell upon deaf ears until French engineer Ernest Deligny heard about it. He went on to set up a mining exploration concern in 1853 with the aim of claiming mining rights through concessions and leases. Two years later it was swallowed up by the Compagnie des Mines de Cuivre de Huelva, of which Deligny was a director. There was early success followed by several major hurdles which saw the company fuse with Tharsis Sulphur and Copper Company, a larger British mining company.

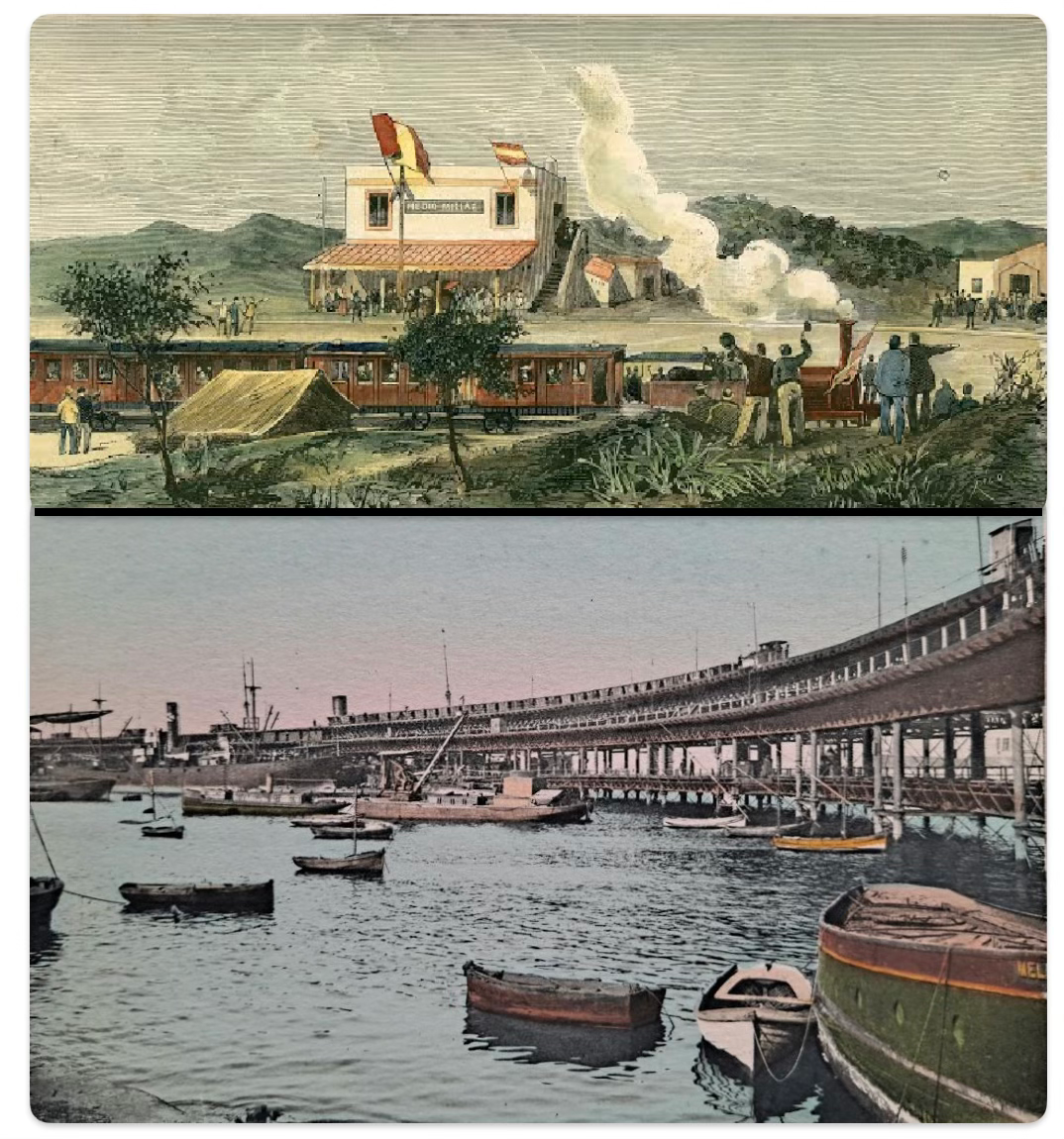

This renewed activity, together with the easing of laws around foreign capital investment proved a boon for the British-owned Rio Tinto Company - competitors to Tharsis - which began mining the area along the Rio Tinto river in 1873. Over the course of five years, three mining railways were built to connect the cuencas mineras, or mining basins, with the port/pier which in turn became important for local exports.

In 1907, Rio Tinto opened Corta Atalaya, which was the largest open-pit mine in the world, employing 2,000 workers and giving birth to its own mining town (eventually destroyed to enable more mining). The company’s main excavation sites were located in the area, and gave rise to the city of Las Minas de Riotinto - known in Classical Antiquity as Urium.

Development

This economic activity was vital in transforming Huelva from a smaller settlement into an urban center. By 1876, Huelva was officially recognized as a city and, by the next decade, passenger railway lines were running to Seville and Extremadura.

In the period between 1850 and 1900, Huelva's population surged from approximately 7,000 to 20,300. In contrast, nearby Cádiz grew from 52,000 to 69,000 over the same period, but its size, growth, and development were influenced by different factors. Nonetheless, Huelva grew at a rate of 190% compared to 33% for Cádiz, and the change was seen in more than just the population. The following were all either British-built or greatly influenced by their presence in the province.

From this era come many of the city's most representative and beautiful buildings, such as the Muelle del Tinto (1876), Hotel Colón (1883), the Reina Victoria neighborhood (1916-25), the old Sevilla station (1888), and the Santa Fe market (1905), among others [3].

Influences

The aforementioned Reina Victoria neighborhood, also known as the Barrio Obrero, was built to house the English and features 274 houses in a British style, with semi-detached homes, and gardens. Originally planned to be mere copies of each other, a secondary design won out and featured more than 20 different kinds of façades, with blended styles made up of Andalusian, neo-Mudejar and colonial architecture [4].

The British are also to thank for Spain’s longest playing football club - Recreativo de Huelva, founded in 1889. However, soon after arrival in 1873 they were already having “kick-abouts”, and by 1878 they had an unofficial club supporting a variety of sports, including tennis which they also introduced to the Spaniards.

They also left their influence on local expressions such as “saber más que Brijan” (know more than Brian) and “tomarse un manguara” (to have a brandy) [5]. The first refers to Dr. Brian, a famous doctor from Rio Tinto and the second is how they referred to brandy - “man water” (likely a back translation of “agua para hombres”).

Conclusion

The British impact on Huelva extended far beyond buildings, ball games, and buzzwords. They arrived with a distinct way of life - speaking a different language, wearing unfamiliar clothes, and operating within a model that clashed sharply with local norms. Yet, they were also “victims” of their Victorian ethos.

The most criticized point of the British footprint is the hermetism of the British, their strict conception of classes and the elitism that they used to not mix, at any level, with the natives, who were excluded from social life [6].

Furthermore, their contributions to mineral extraction, worker organization, and industrial practices offered a stark difference to national practices. Yet, the strip mines also stripped away a sense of Spanish identity, turning local resources into impersonal commodities exported abroad. While Jerez wine retains its provenance on every bottle, the materials extracted in Huelva were disconnected from their origins and shipped abroad to aide industrial powers [7].

This disconnect was multiplied by the fact that much of the profit bypassed Spain entirely, leaving little reinvested in local or national economies - contrary to the Mining Law’s intent. Opportunities for local companies to participate in the wider supply chain, from processing to transportation, were lost as the British enterprise internalized nearly every aspect of production. Even the everyday needs of British workers were met by their employer, further limiting economic diversification in the region.

As Spain faced imperial decline, companies like the Rio Tinto Company - backed by Rothschild capital - grew globally. Meanwhile, Huelva saw minimal long-term economic transformation.

Today, Huelva’s British influence exists largely in its architecture and historical footprint, with just over 1,000 British residents comprising 0.2% of the city’s population. The industrial revolution came late to Spain, mostly benefiting regions like the Basque Country and Catalonia, while Southern Spain remained economically stagnant. The mineral wealth extracted during the 19th-century boom facilitated growth across Europe, but for Huelva and much of Spain, the legacy is one of missed opportunities and externalized gains.

Additional Information

1 - La internacionalización de las minas de Huelva

2 - one claim says British workers in Vigo were the first to bring football to Spain

Sources

1 - La Historia del Puerto de Huelva (1873-1930) (pdf)

2 - Británicos en Andalucía

3 - Crecimiento y evolución de la ciudad de Huelva

4 - El Barrio Reina Victoria, una de las joyas del legado arquitectónico inglés en Huelva

5 - La esencia del legado británico en Huelva

6 - El camino de hierro de Río Tinto, la modernidad 'british'

7 - La presencia ''inglesa'' en Huelva: entre la seducción y el abandono (pdf)