Under a treaty aimed at redrawing European borders post-World War I, the region of South Tyrol was transferred from the Austrian-Hungarian Empire to Italy. This move was part of a pre-war treaty, where Italy agreed to join the Allies in exchange for new territories. At the time of this cession in 1919, South Tyrol was predominantly German-speaking, with about 90% of its inhabitants using German as their first language. This fact presented a challenge for Italy as it sought to integrate these new territories into its culture and language as well as incorporate 220,000 German (and Ladin-speaking) Tyroleans into Italy.

This integration process, known as Italianization (or Provvedimenti per l'Alto Adige), was actually a forced assimilation of the majority to adjust to the minority, in what might be deemed - at least regionally - an upside-down cultural hegemony. Its aim was not merely to Italianize the region but rather to ban both Austrian influences and the German language across South Tyrol. Its implementation occurred in a gradual manner, starting with administrative changes, but escalated sharply with Mussolini's rise to power in 1922.

Due to Europe's shifting borders, Tyrol, which was largely under Habsburg rule since the 12th century, was divided into three regions post-1919: the Austrian state of Tyrol and the Italian region of Trentino-Alto Adige (South Tyrol and Trentino), initially known as Venezia Tridentina until 1947.

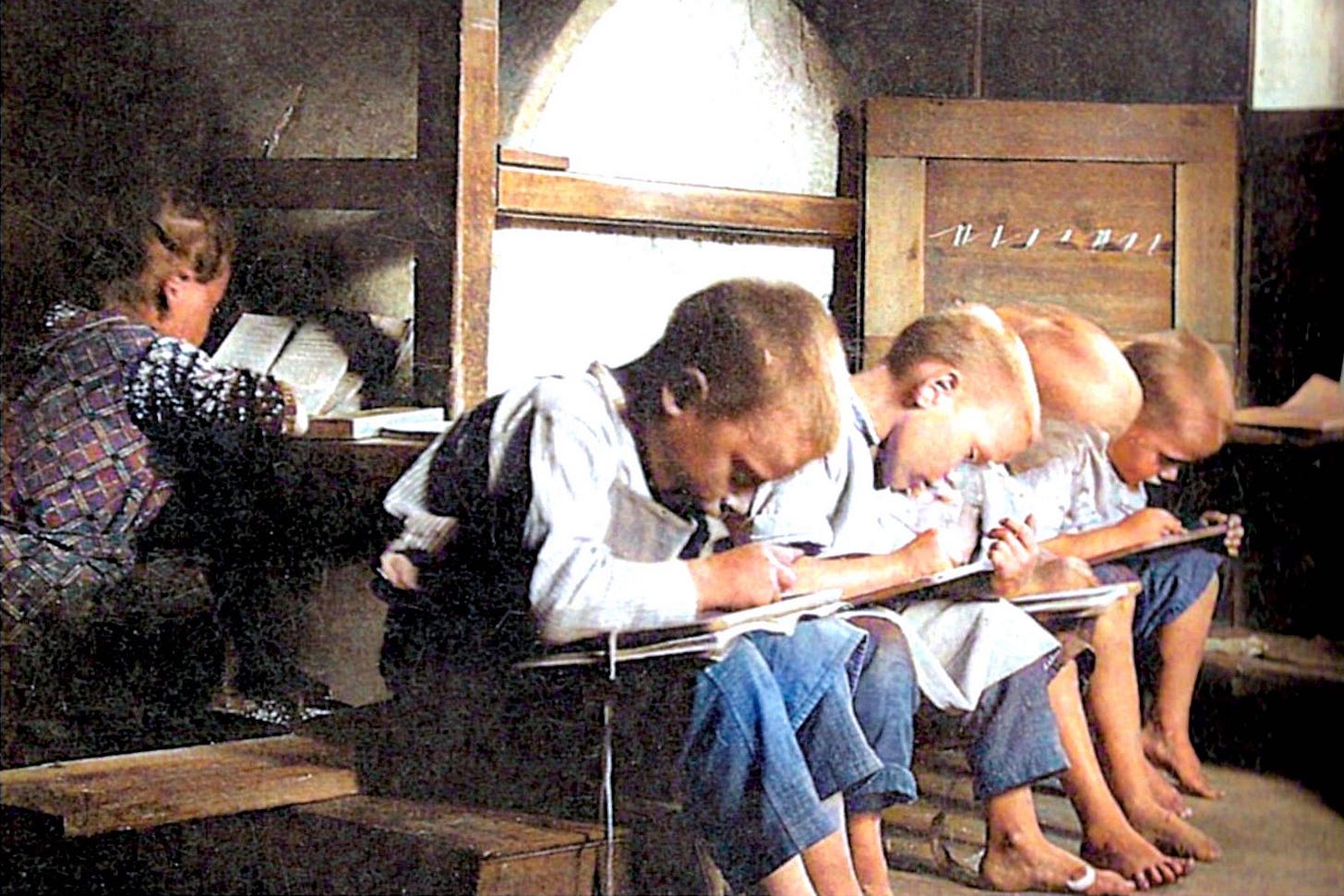

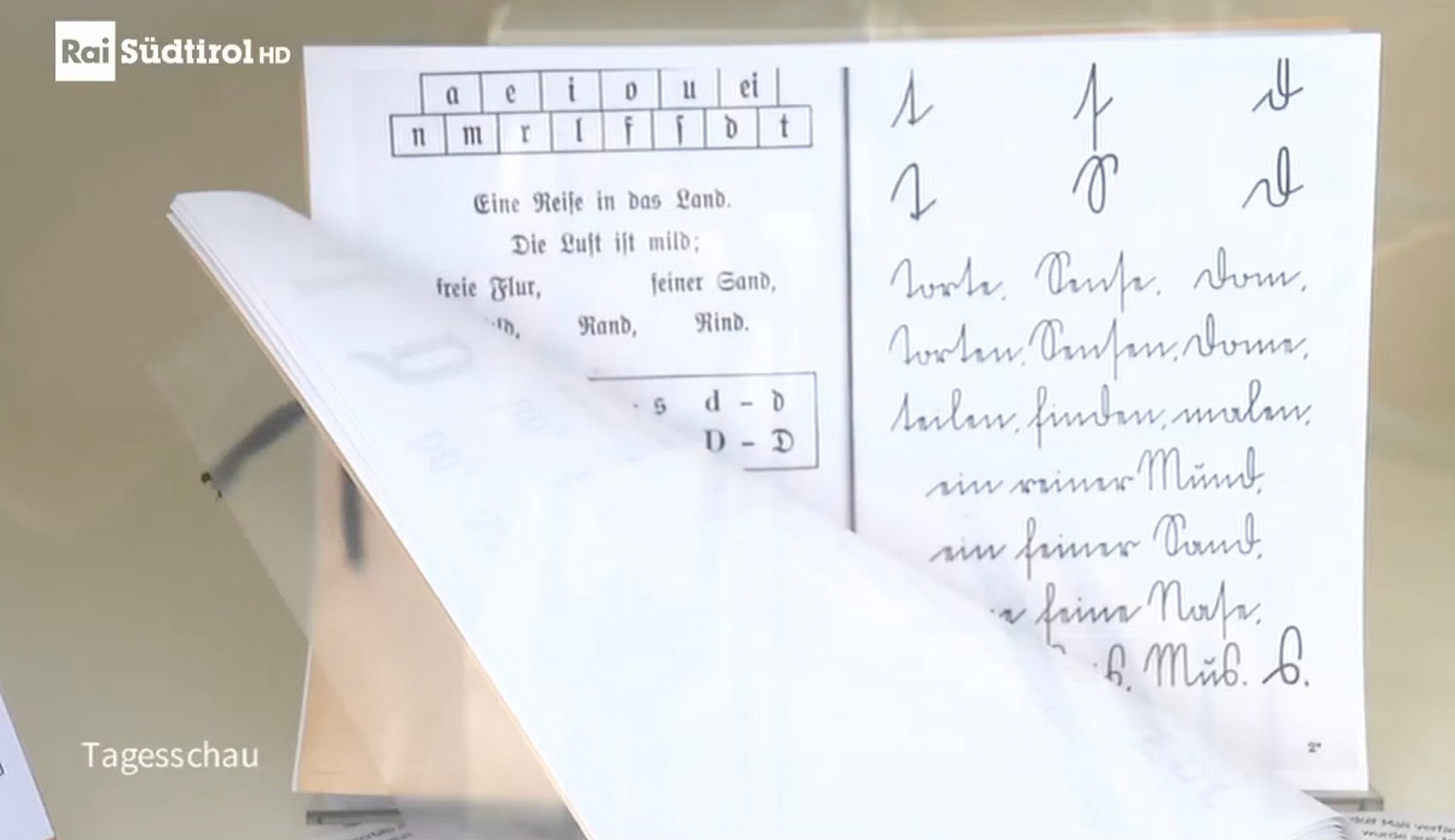

Catacomb Schools

In the realm of education, the 1923 Gentile Law centralized and standardized Italy's school system, aligning it with Fascist ideology. The law, combined with Italianization, brought about the banishment of German as a language of instruction in 1925, which affected 30,000 students. As a result, it led to the creation of an underground network of secret German schools known as Katakombenschulen (catacomb schools) or Notschulen (emergency schools) where 5,000 children studied at least two hours per week. Among the driving forces leading the effort for clandestine learning was priest Michael Gamper who said:

If we are no longer allowed to speak German in public, then we will do as the first Christians did; we will go underground, we will go into the cellars, we will go into the catacombs [1]

Aside from financing, via a German cultural association - the VDA, books had to be spirited among farms and convents, and teacher aides had to be procured. Two-thirds of the estimated 500 young female volunteers were soon smuggled in from both Germany and Austria.

These verboten hotbeds of grammar drills, declinations and case systems reportedly started in 1923 when the proverbial writing was already on the wall. Teaching was done in homes, farmhouses and churches, in small groups to minimize detection, with lessons mostly held late in the evening. The sessions operated under the constant threat of raids, leading to a chaotic learning environment where children had to quickly hide materials or escape [2]. When adults were caught they were fined, imprisoned and at times deported from the Kingdom of Italy or to Lipari, near Sicily.

Wider Oppression

The Italianization scheme in the Trentino-Alto Adige region went longer and harder than one might imagine. Mussolini said his desire was:

[…] to push the Italianization of the region to the maximum, that is, to profoundly and durably alter its physical, political, moral, demographic character; that is, replacing, or at least mixing, the current German majority, with an Italian majority or a very strong minority that takes away from the region the character it has today, and which is predominantly German [3].

Eventually, the Italian government brought in swaths of Italians to replace locals in public positions, leading to cultural suppression and land expropriation for industrial purposes. This disenfranchisement pushed some Tyroleans towards Nazism. In 1939, under the Berlin Agreement, they faced an ultimatum: move to Germany or stay and accept Italianization, with rumors deterring the latter choice by suggesting deportation to Sicily.

The "vote" saw 86% (or 213k) opting for Germany, and while only 35% (or 75k) actually relocated, upon arrival they faced harsher realities than what was promised. The results empowered the Nazis locally, leading to a dual power structure with Italian authorities allowing Nazi activities, including the opening of German schools. This left many German-speaking Italians caught between two oppressive forces [3].

Conclusion

It would take until after the end of WWII for the German-speaking population of the region to secure cultural and linguistic autonomy, initially promised by the 1946 Gruber–De Gasperi Agreement and enshrined in the 1948 Constitution. This was later reinforced by the 1972 Autonomy Statute, which realized these promises by granting concrete legislative and administrative powers. However, full resolution of some issues wasn't achieved until the 1992 acknowledgement (the kind of timeline that showcases Italy’s famous “lentocrazia”, or slow bureacracy).

Following the 100 year remembrance of the negative effects of the Gentile Law, there was a ceremony held in Bolzano in 2023, in appreciation of all the Catacomb teachers, as well as a suggestion for a way to honor them. The head of the South Tyrolean Rifle Association stated:

Let us look back with humility and gratitude and simply be thankful to these almost 500 teachers for their selfless dedication. This dirty era deserves a memorial, and the heroic teachers of the Catacomb Schools should have a monument erected right in the center of Bolzano [4].

Linguistically, nearly 60% of South Tyroleans today speak German as their first language and 22.6% speak Italian. Across the 116 municipalities of South Tyrol, 102 are German-speaking majority. Such statistics hint at perhaps the real memorial to the efforts of the underground schools: the living one that can be heard across the region.

Additional Information

1 - Michael Gamper (Wikipedia)

Sources

1 - Documentary on schools in South Tyrol, Part 1 & 2 (German)

2 - Le scuole clandestine durante il fascismo

3 - La resistenza sudtirolese, parte #1

4 - Danke für Euren Einsatz!

5 - Popolazione e aspetti sociali, 2024 (pg 116, pdf)