Ten minutes by boat from the famous Piazza San Marco in Venice lies the small island of San Servolo [1]. Known first and foremost as a Benedictine monastery and later as an asylum for the insane, the island has played many roles.

It’s hard to imagine that the city of picturesque canals and gondolas, known for centuries as the Serenissima, or the Most Serene, would also be home to a place that evokes an opposing sensation. The asylum - which gave birth to the name isola dei matti, or island of crazies - was a fixture of Venice for around 250 years. The history of isolation and its connection to the city, however, are centuries in the making.

Isolation by any other name

The idea of isolating undesired people on an island wasn’t a novel one, as the word ghetto comes from the Venetian ghèto, due to the world’s first Jewish ghetto existing in 1500’s Venice. In fact, even the word “quarantine” comes from the Venetian language, where it referred to a 40-day isolation period for the passengers and crew of ships going to Venice during the Black Death. The initial term was trentino, referring to a month-long isolation but it was later extended to 40 days. These locations of isolation became known as lazarets and the very first one was Venetian.

The forty-day quarantine proved to be an effective formula for handling outbreaks of the plague. According to current estimates, the bubonic plague had a 37-day period from infection to death; therefore, the European quarantines would have been highly successful in determining the health of crews from potential trading and supply ships [2].

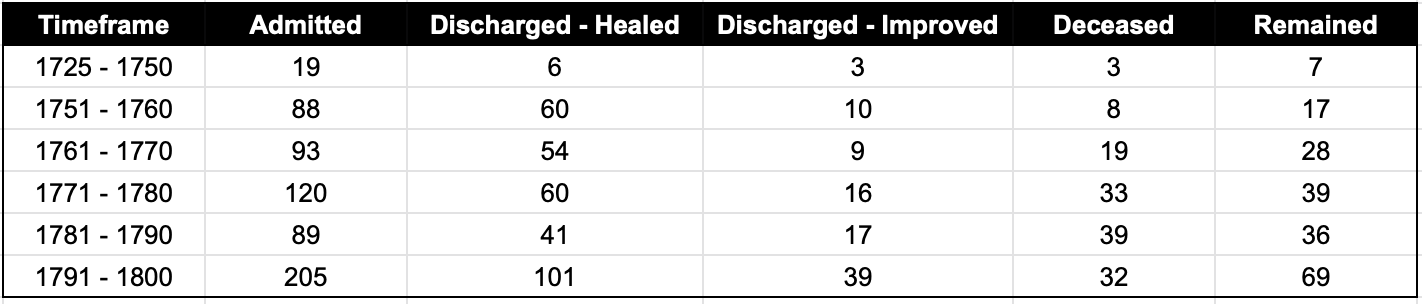

Regarding how many were “isolated” on the island of San Servolo over the centuries, estimates have proven hard to come by, but one English-language travel site puts the number at over 200,000. An Italian book on the history of poor and unwell citizens of Venice puts the number - at least during a 70-year period following the opening of the asylum - at around 600, as can be seen in the translated table below.

Some reasons for admission led to short stays. For example, pellagra, which comes from a severe lack of vitamin B3, was the main cause of the mental imbalance of many inpatients, and merely eating more regularly was enough to heal them.

Between its existence as a monastery and an asylum - and a decade before the sanatorium was created - a military hospital existed in its place, due to the continuing war against the Turks. In 1725 the hospital opened to Venetian nobility after a wealthy, mentally-ill man who requested care was granted a space there in exchange for payment.

Previously, the mentally ill would have ended up either in jail or otherwise isolated from society. Those who were unlucky enough to be both poor and mentally unwell (or just incarcerated) eventually ended up in a fusta, a disarmed and dilapidated ship anchored in front of the Palazzo Ducale. It was only in 1797 that the asylum opened to all patients and by the end of 1808, the military hospital was officially transferred to the city, leaving only the asylum in its place.

For two and a half centuries, the sanatorium at San Servolo would serve the mentally-ill. At the turn of the 20th century, change would come - slowly then all at once - to the Italian health system, causing the doors of the asylum to officially close.

Political Solutions

In 1904, the Giolitti Law came into effect, as a means of better defining and streamlining rules around patient admissions and releases. Unfortunately, the law was more about protecting society and did little to advocate for patient rights and living conditions. But that would change some 70 years later.

In 1978, the Italian government started reforming its entire psychiatric system, under the Basaglia Law, named after the main supporter of the reform, Venetian psychiatrist Franco Basaglia.

[The law] contained directives for the closing down of all psychiatric hospitals and led to their gradual replacement with a whole range of community-based services, including settings for acute in-patient care [4].

Regrettably, mental hospitals for the incarcerated did not fall under the statute, as Basaglia’s crusade was more centered around health than it was justice. Known as OPGs, these judicial psychiatric hospitals were to be replaced with REMs (Residence for the execution of security measures) as a more patient-friendly alternative. While many changes took place due to the Basaglia Law - and many other countries looked to Italy’s reforms to model their own systematic overhauls - the official closure of OPGs in Italy only took place in March 2015. Even that date wasn’t held to, as several months following that date, not all OPGs had become REMs [5, 6].

Other Roles

As for the island, from 1978 to the 1990s, its structures were left in total abandon until a government decree led to its restoration. In 2004, the government created an institution to protect and manage the island, and it has led to one of Venice’s most beautiful little islands being utilized in a handful of ways, to the point that between 120 to 150 events take place there annually.

Another important permanent cultural attraction is linked to VID, Venice Innovation Design. Established at the site of a Benedictine convent, San Servolo has also hosted several National Pavilions of Biennale of Art and Architecture for over a decade, various collateral events, temporary exhibitions of photography, painting and sculpture, music festivals and video presentations [7]

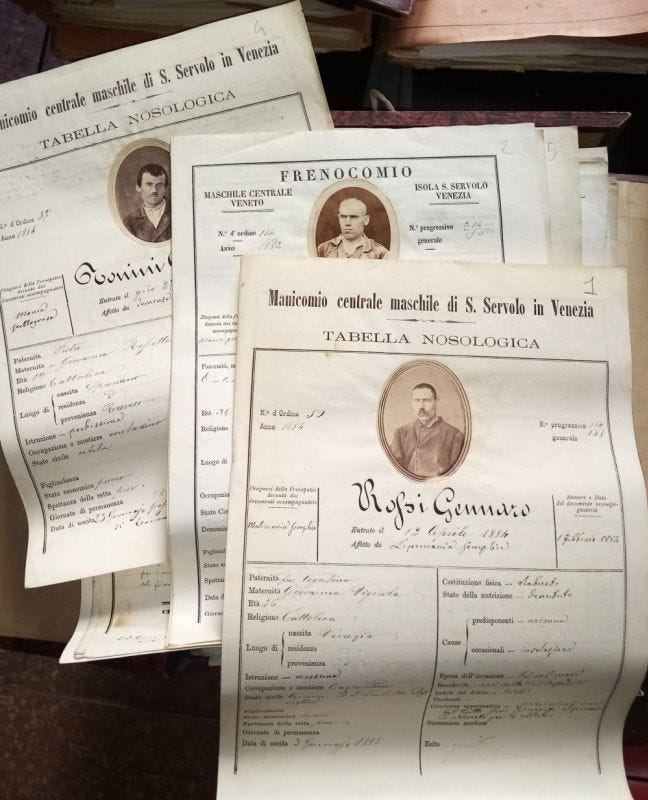

One of the island’s principal attractions since its redevelopment, however, is its museum. In 2006, a wing of the former convent was transformed into a museum of the insane, showing how the mentally unstable were medically treated during nearly three centuries.

[The museum] is divided into nine sections: the Laboratory, the Ambulatory, Didactic Products, Sickness Therapies, Straightjackets, the Sick, Lodgings, Pharmacy, and Anatomical Theater. The archives hold photo albums of patients from 1874 through to the 20th century... [8]

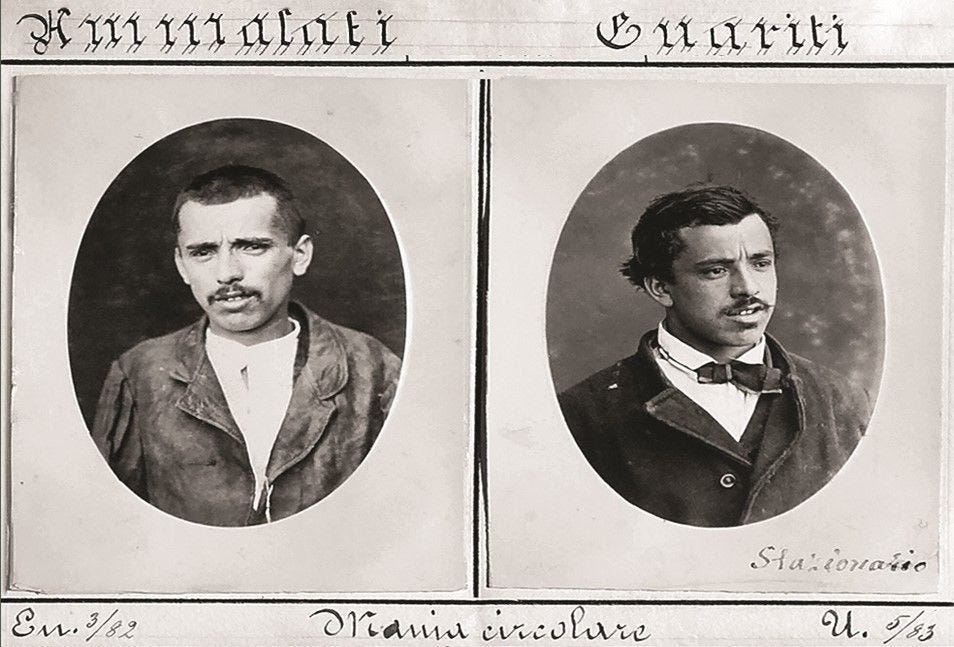

The photo albums include comparisons of the patients, as they were when they entered, and later left, the asylum, as shown below. The archives also hold the testimonies of the therapies which patients undertook, daily.

The island - showing its place in the collective memory of Venice - is still sometimes referred to as the isola dei matti today. So much so that, at one point, the asylum’s fame apparently gave rise to the phrase, se non fai il bravo ti mando a San Servolo (if you aren’t good, I’ll send you to San Servolo). Whether being sent there is a good or bad thing depends entirely on which version of the island is being discussed: the convent, the hospital and asylum, or the place of learning and culture that it has become today. One thing is for sure, San Servolo has always been a place of before & afters, of salvation and transformation.

Additional Information

1 - The current area the island takes up is almost 10 times larger than its original size due to man-made territorial expansion.

Recommendations

The film La Pazza Gioia (aka, Like Crazy) is about women who were former patients of a sanatorium, and now living in a CSM (or, Mental Health Center). Also recommended, Si Può Fare (aka, We Can Do That), a drama about a co-living collective in the early 1980s, set up to deal with the former patients of mental hospitals.

Sources

2 - A Brief History of Quarantine

3 - Per la salute di que’ poveri infermi: Tre secoli di hospitalità dei Fatebenefratelli a Venezia

4 - Basaglia Law

5 - L’Unione delle Camere Penali Italiane all’attacco: «Riforma degli Opg mai partita»

6 - Dalla Basaglia alle R.E.M.S.: l’evoluzione normativa e culturale del sistema di assistenza al paziente psichiatrico-forense

7 - Un mondo in un'isola: San Servolo

8 - San Servolo Insane Asylum Museum

9 - Gli ospedali di S. Servolo (official site, English)

10 - San Servolo, Venezia. Da luogo di segregazione a isola polifunzionale