The rise & fall of student nations

Wandering scholars: a historical perspective on academic mobility

The tradition of the peregrinatio academica - or academic pilgrimage - was a defining feature of its time. Elite mobility in the Middle Ages was generally afforded to two groups of people - nobility and scholars - so much so that it was seen as a rite of passage to travel Europe. The nobility did it via the Grand Tour where the aim was gaining cultural refinement through experience, while would-be scholars sought out institutionalized, formal education through the great universities.

One can think of the peregrinatio as a wandering Erasmus program, only amplified. In the medieval period, universities were relatively few and often specialized (ex. Bologna for law, Paris for theology, Salamanca for medicine), so in order to curate their own interdisciplinary education and learn from the best, travel was essential. Journeys were facilitated by regional corporations that united students from the same area or who spoke the same language.

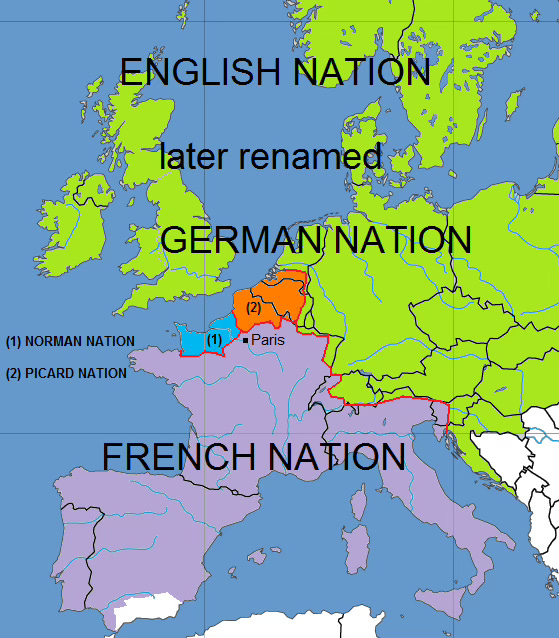

Student nations of France

Academically rooted “nations” were more than informal, self-organized student groups, they were central to the structures of medieval universities. They provided fraternity, legal protection, privileges (including the ear of the King and Pope), self-governance, mutual assistance, alumni networks and reputation. The collective identity framework that nations embodied helped students navigate the complexities of foreign cultures and laws, much like guilds helped artisans maintain standards and assert their rights within their trade.

Different universities structured their nations differently, both in number and country of origin. The University of Bologna, where the concept of nations is thought to have originated around 1180, was such a place. They had just two nations (one for Italians not from Bologna, and another for foreigners) and 31 sub-nations. In contrast, the University of Orleans had 10 nations in the early 1500s until France’s highest legal authority - the Parlement de Paris - ruled that six had to close.

Some nations, like the powerful German one in France, wasn’t actually German - at least not in its entirety or even majority, depending on the era. It was administratively divided into Superior Germania (actual Germans) and Inferior Germania (ex. Dutch, Belgian). At times, the nation’s regent, or representative among professors, was from the Inferior group, which caused protests among the Superior class.

At the Universities of Paris and Orleans, there were the French, Normans, Picards, and the English (later named German) nations. At Orleans, registration with a nation was mandatory because the university only recognized students who enrolled in one of the four nations. Additionally, it was a requirement by the local government, which sought to keep an eye on young foreigners temporarily residing in the city. Many of the well-to-do students treated their journey through the universities as more of a gap year (for the experience’s sake) than a serious endeavor. Those simplices, or non-ambitious learners, who slacked off were not immune from consequences.

On the despair of parents, through private letters:

"You waste your time wandering around the city on horseback, playing dice (a game generally prohibited for students), playing cards, you spend your money on royal clothes, on soft furs, showing your great foolishness.”

“I heard, not from your teacher, but from some trusted people, that you do not study seriously, that you enjoy playing the guitar, that you frequent inappropriate places (prostitution included)”

A strict response from a student: “Those who stay at home judge the absent as they please, while sitting at the table, enjoying meat stews and plenty of bread, completely forgetting that someone, subjected to the harsh rules of the school, is oppressed by hunger, thirst, cold, and nakedness.”

Sometimes the father's scolding takes on a pathetic tone: “Your parents are now full of sorrow and deserving of pity… you shorten their lives…”

If a student, arriving in a city, failed to register with a nation within a set period of time - such as six weeks - they were blacklisted by the nation. In some instances at Orleans, the bailiff would be notified when registration wasn’t heeded. The Germanic nation, in fact, had an informal agreeement of mutual aid with the French government. The nation’s members were shielded from persecution and allowed special privileges, while the crown secured a loyal and influential group of students.

Such privileges included voting rights, access to legal assistance and loans, as well as exemption from taxes, tolls, and the droit d’aubaine (inheritance tax on foreigners). They also received royal protection throughout France. In 1583, King Henry III granted noble students the right to carry swords, similar to the French nobility. King Henry IV reaffirmed these rights in 1600, guaranteeing their safety and immunity from capture or ransom, even in times of war, ensuring they could travel freely.

Students from the most notable families were asked to register almost immediately after arriving in the city, so that the record books could be adorned with their names. Other students that took part in the nation system would only attain recognition later in their life, such as Nicolaus Copernicus and Miguel de Cervantes.

The fall of nations

Whlie student nations still exist in countries like Sweden and Finland, or in different configurations such as American fraternities and sororities, they died out long ago in Latin Europe. Medieval French chronicler Jacques de Vitry wrote of the in-fighting among nations in Paris:

They affirmed that the English were drunkards and had tails; the sons of France were proud, effeminate and carefully adorned like women. They said that the Germans were furious and obscene at their feasts; the Romans, seditious, turbulent and slanderous; the Sicilians, tyrannical and cruel. After such insults from words they often came to blows.

Belgian sociologist Léo Moulin adds:

Thus, all of Europe was ridiculed by the Europeans themselves. It is needless to say that such serious insults - spoken in Latin - accompanied by obscene allusions to the mother of the person in question, would have been drowned in blood.

Though student nations have mostly disappeared, traces of them can be found in modern academic and social organizations as well as study abroad programs, reflecting the historical roots of student communities and networks.

Sources

1 - Peregrinatio academica

2 - Professeurs et étudiants étrangers dans les facultés de droit françaises (pdf)

3 - Les registres-matricules de la nation germanique de l’ancienne Université d’Orléans

4 - Medieval Sourcebook: Jacques de Vitry: Life of the Students at Paris

5 - Nationes (Wikipedia, IT)

6 - La vita degli studenti nel Medioevo (Léo Moulin)