The island of Madeira in the North Atlantic Ocean is unique in many ways, one of them being its intricate network of irrigation channels - known as levadas - that wrap around the rugged escarpments. Originally devised in the 15th century when the island was first settled, they carry rainwater - both freshly fallen and stored in underground aquifers - from the wetter, mountainous northern side to the flatter, drier agricultural lands in the south. Over time, this remarkable irrigation network grew to an impressive length of 1,400 kilometers, on an island spanning just 756 square kilometers.

These levadas, integral to Madeira’s early agricultural success, channel water captured and held by the Laurisilva subtropical cloud forest. This unique forest absorbs moisture from rain and mist and releases it through springs, streams, and aquifers. Thousands of poios - small terraces with arable soil supported by basalt rock walls - were built across the steep slopes of the island to create farming surfaces [1]. Over time, this method of terracing spread throughout Madeira, transforming its landscape and making agriculture possible.

The origins of Madeira’s levadas

The early settlers of Madeira, primarily from the Douro and Minho regions in Northern Portugal, brought with them knowledge of irrigation. This expertise helped them construct the island’s first levadas. Interestingly, the idea of levadas was not new to Portuguese agriculture; for instance, the Levada do Piscaredo [3] was constructed in the 13th century near the Douro River during the reign of D. Afonso II.

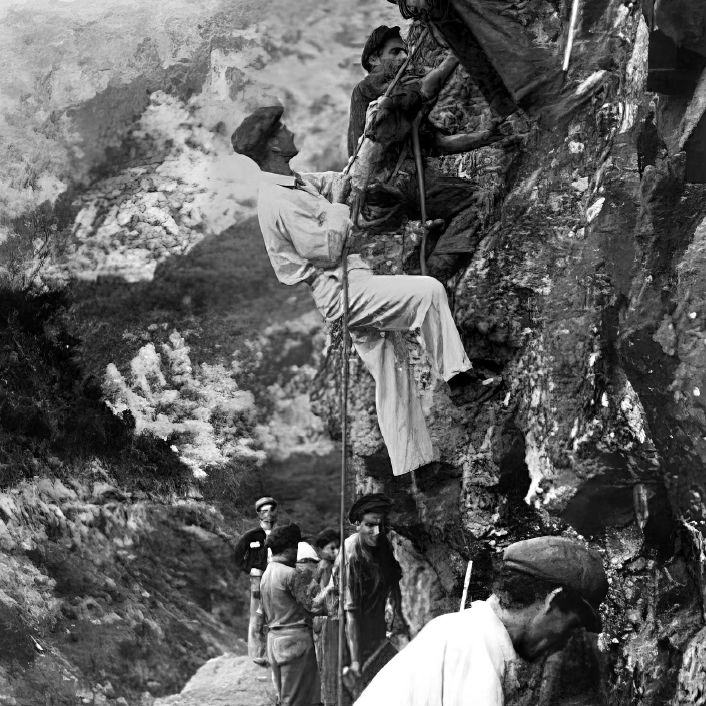

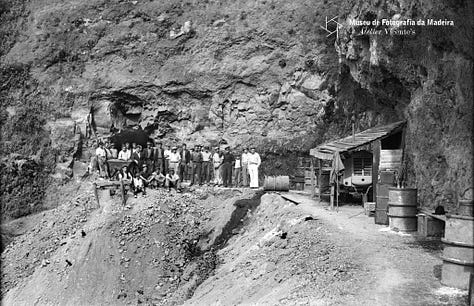

Building levadas on Madeira, however, posed unique challenges. The work was perilous, often requiring laborers to dangle from ropes while carving out channels along the steep mountainsides - sometimes at heights of 500 meters. The responsibility for constructing and maintaining the levadas fell to rocheiros (excavators) and levadeiros, with early labor provided by convicts and slaves.

The levadeiros became so renowned for their expertise that Afonso de Albuquerque, the viceroy of Portuguese India, once requested from King Manuel a group of Madeiran workers to help divert the Nile and conquer Egypt. This ambitious request, however, was denied [4].

Agricultural evolution

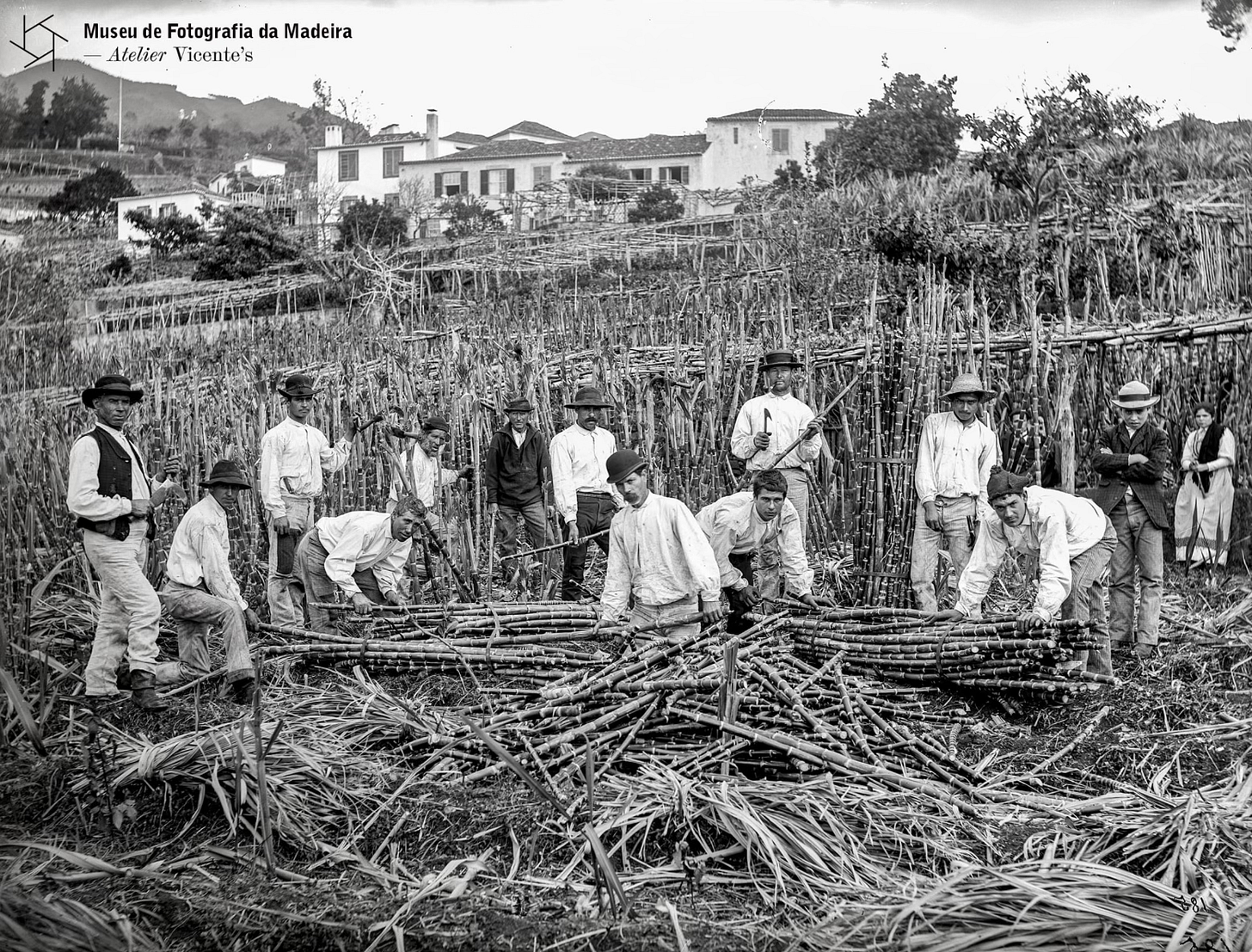

The purpose of the levadas evolved over the centuries to meet the island’s changing needs. Initially, they were built to irrigate wheat and sugarcane fields, establishing Madeira as Europe’s largest sugar producer during the 15th and 16th centuries. Sugarcane production became such a massive enterprise that it attracted bankers and merchants from across Europe. However, the environmental cost was staggering - by 1520, 75% of Madeira’s forests had been destroyed, as sugar production required burning 50 kilograms of wood to produce just one kilogram of sugar. Moroccan Berbers were initially brought in as laborers, followed by West African slaves when they proved to be a cheaper workforce.

When sugarcane became cheaper to grow in Brazil, Madeira shifted its focus to grape cultivation. The island developed its renowned wine industry, which became a staple on ships during the Age of Exploration. This fame was partly accidental - Madeiran wine required fortification to survive long voyages, and the heat in ship holds was discovered to improve the wine’s flavor.

Sugarcane made a brief comeback in the 19th century due to vineyard diseases, but by the 20th century, another crop had taken over as the dominant one on Madeira: bananas. Now a symbol of the island’s agricultural identity, they employ 21% of the working population, across 10,000 farms [6].

From private to public

In the first four centuries following the island’s initial colonization, the arduous construction of the levadas was left to private initiative, carried out by owners of springs or the lands to be irrigated – either individually, or grouped into associations of heréus, co-owner farmers who own a share of the levada water and pay for the preservation of the waterway, electing an administrative committee from among their number [7].

In 1947, the levadas were formally placed under State control with the establishment of the Administrative Commission for the Exploitation of Water Resources of Madeira. This shift allowed for the creation of hydroelectric power plants, further modernizing the island’s infrastructure. However, public investment in levada construction had already begun more than 100 years earlier, with the construction of the first publicly funded levada.

Today

The estimated 200 levadas on the main island exist not only thanks to the arduous work of the men who built them, but due to the unique characteristics of the Laurissilva forest and its vegetation. Through an ecological process known as hidden capture, the environment is one that collects, retains, and slowly releases water, meaning it’s a stable system that offers a continuous water supply, perfect for irrigation purposes. Portuguese historian Gaspar Frutuoso, who witnessed the early colonization of the island, said that it burned for seven years straight, in an attempt to lessen its super dense vegetation. If true, one can imagine that the current day flow of water is less intense than originally witnessed.

Today, water from the levadas doesn’t only sustain irrigation, but also contributes to the 33% of the island’s energy that comes from renewables. This feat is accomplished via four hydroelectric power plants, as well as wind and solar systems.

The volcanic origins of the island’s jagged terrain, combined with the orographic effect - where the northeast trade winds bring moisture to its subtropical microclimates - create the ideal conditions for the lush Laurel forest. The forest allows for hidden capture, which enables life and livelihood.

All the elements combined have led to lots of tourism where one of the top attractions is the opportunity for hiking, including along ten of the 200 levadas [8]. The more than 5.2 million tourists in 2023 converted into 652.7 million euros in revenue for the island and its people [9]. The millions of tourists who visit Madeira each year are drawn not only by its stunning landscapes but also by the interplay between ecology and sustainable development - a carefully balanced process that respects the nature of the island, much like the levada system that has sustained it for centuries.

Additional Information

1 - The Birth of Macaronesia (Ambulatin)

2 - Visita Guiada - Ilha da Madeira, Levadas (48m) | Youtube

3 - A few other countries have irrigation channels similar to levadas. Some examples are the Bisses of Switzerland, the seguias of Morocco, and the acequias of the Canary Islands.

Sources

1 - Madeira 1440 a 1540: Escravos, açucar e capitalismo desenfreado

2 - Trabalhos de construção da Levada do Norte 1952

3 - Piscaredo Watercourse (pdf)

4 - Estudo Fitogeográfico dos Jardins, Parques e Quintas do Concelho do Funchal

5 - Rum da Madeira: História

6 - Banana production in Madeira (pdf)

7 - Levadas of Madeira Island

8 - Madeira Hiking

9 - Turismo da Madeira bateu todos os recordes em 2023