The iconography of the Feria de Abril

Unpacking the material culture of Seville’s famous festival

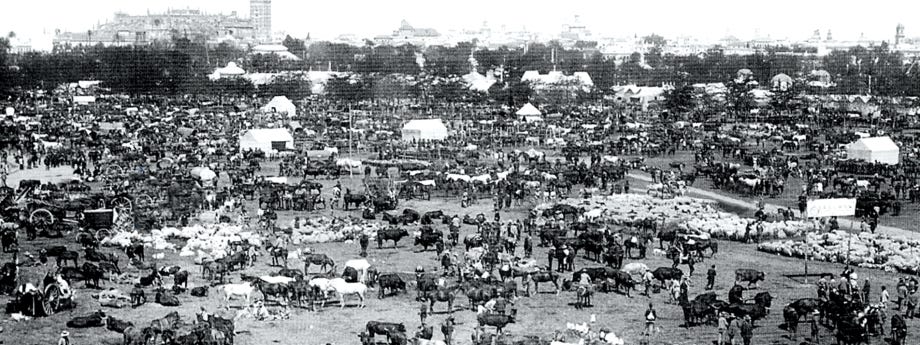

The iconic Seville Fair dates back to 1846 when two councilmen sought to boost the local economy by organizing a cattle market. This initiative, known as the Feria de Ganado, revived the centuries-old tradition of annual fairs dating back to the time of Alfonso X, promoting commerce and incentivizing farmers and cattlemen to improve their offerings.

The start of the 19th century had been particularly rough for Seville, beginning with a yellow fever epidemic that decimated a third of the city’s population, followed by a drawn-out French occupation. Despite being Spain’s third largest city in terms of population, industrialization arrived late, its streets were unsanitary and poorly maintained, floods frequently destroyed homes and warehouses and urban infrastructure was far behind other provinces. The population was largely poor, unemployed, and hungry, suffering a high rate of untimely deaths. An 1840s bombing campaign linked to a war of succession didn’t help matters. It left its people in need of a reason to celebrate, and the Feria de Ganado filled that void.

The first edition was held at the Prado de San Sebastian, on the edge of the city, attracting 25,000 spectators and featuring 19 marquee tents, or casetas, which resembled the stables one might find at a livestock event. By the second year, the cattlemen were already making formal complaints about the onlookers who took advantage of the occasion to sing, dance and otherwise have fun. Year after year, those that were there to make deals were slowly edged out by merrymakers and vendors of food and entertainment until a separate area could be allocated for the business of livestock. Eventually, over the decades, even that was phased out.

Despite the change in focus, it took 30 years for the fair to start the long process of forming a cohesive aesthetic. This began, in part, due to the first offical visit in 1877 by Queen Isabel II who had originally signed the decree allowing the fair to happen. The main architectural and design elements that have come to symbolize the Seville Fair are the tents and their decorative panels, the paper lanterns illuminating the rows of tents, the main gate and, to a slightly lesser extent, the horse-drawn carriages, and posters. Typical female attire includes flamenco dresses with ruffles, and Manila shawls over the shoulders, as well as traditional Andalusian hats for the men.

Also present are depictions of dancing, sherry wine; archetypes like Carmen (of both literary and operatic fame), gypsies, bullfighters, or the Sevillian majo (an elegant and smartly-dressed male type straight out of the Romantic period). Much of what exists in the popular imagination of both Spaniards and foreigners in regards to Seville and the region at large was formed via artistic and literary styles like romanticsm and costumbrismo, with the latter depicting everyday life, customs and traditions [1]. There was also a reciprocal process at play in which foreigners romanticizing Spanish culture was fed back into the national conciousness, whereby external perceptions influenced internal traditions.

Today’s aesthetic is a product of many iterations and styles, forming part of the popular imagination, where each element developed separately but not in a vaccum.

Casetas & Pañoletas

The defining singular element of the Seville Fair is surely the marquee tents and their decorative panels, known locally as casetas and pañoletas. The roofs, awnings and the side drapes are an unmistakable red-and-white (or green-and-white) striped pattern, with a triangular wooden panel and its accompanying design motifs. When studying old images, one can see a more simplified but standard visual framework was already in place by the turn of the century.

There are three explanations as to how they came about. One says that the Duke of Montpensier, who was Queen Isabel II’s brother-in-law and had moved to Seville in 1848, inspired copycats after opening the first private caseta in 1853. The issue is that the only ones copying the Duke were other wealthy people who wanted their own private tents. The second version says that the Álvarez Quintero brothers also inspired copycats after premiering their traditionally Sevillian country house-styled caseta in 1904. And the third is that artist Gustavo Bacarisas designed the more standard version, although this seems to be confused with the fact that he is known as having designed other elements. Regardless, it wasn’t until 1983 that guidelines were dictated for authorized elements with their precise measurements and color-combinations.

Speaking of Bacarisas, the Gilbraltar-born artist was, in fact, responsible for the decorative panels, or pañoletas, on the front side of every caseta, which he designed in 1919. The pañoletas are required to use traditional baroque motifs on a white background, which may include a title or emblem.

The caseta interiors, however, were open to interpretation by the owners of the particular tents [4], which isn’t to say that layouts aren’t shaped by socio-cultural norms. Interior elements usually include lamps, decorative flowers, lacework, mirrors, traditional wooden chairs and tables, old pictures, paintings or posters, and painted or fabric-covered walls. Unfortunately, casetas-as-a-service are now a thing, with companies offering full-service, kitted out versions for rent but perhaps it was inevitable now that there are over 1,000 public casetas.

As far as who all these casetas belong to:

[They] usually belong to groups of friends, brotherhoods, associations, schools, political parties, unions... and use them as a means of financing their activities throughout the year [5].

Farolillos

The other emblematic element created by Bacarisas was the paper lanterns, or farolillos, that light up the entire fair, and which have been called Chinese in design. They were commissioned in 1877 for Queen Isabel II’s previously-mentioned visit to the fair yet only really made their mark when the fair’s illumination switched from gas to electricity in 1883 [6].

Pasarela & Portada

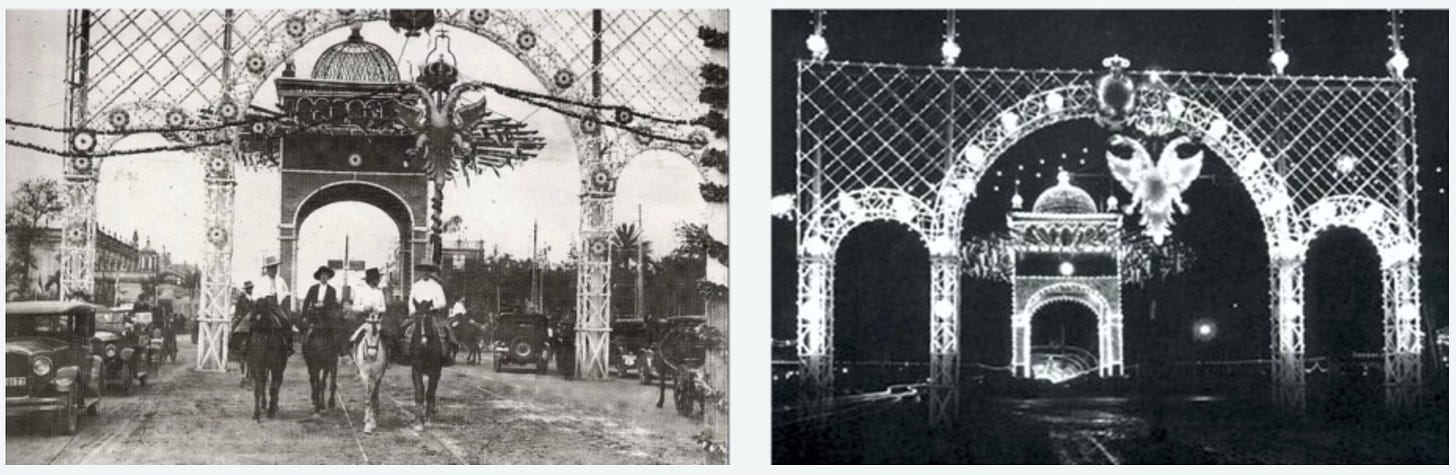

Over the centuries of the fair, there have been several iterations of its main entrance, from the Puerta de San Fernando (a gate, part of Sevilla’s defensive wall, 1847-1868) and arches decorated with flowers (1869-1895), to iron walkways (1896-1920) and a mix of structures (giant street lights, fountains, towers and illuminated ephemeral entrance gates, 1921-1948). From 1949 to the present, the latter - which is to say the illuminated gate - has been the most emblematic in the event’s history.

Yet one could argue that the most iconic entrance came just before the turn of the century. In 1896, a large, 81-ton iron structure known as the Pasarela (pedestrian walkway, pictured above) was built, as a decorative, unofficial entrance to the fair, with four staircases and hundreds of light bulbs that illuminated the central kiosk. Inspired by the Eiffel Tower, it was set up at the end of San Fernando Street, marking the access point to the casetas. However, by 1920, it was torn down and sold for scraps due to a planned urban expansion of the area.

In 1949, the Portada (illuminated main gate) was put in its place, to officially mark the fair’s entrance, and each year a new version has been built in the same place. Much like other large, annual events like Rio’s Carnival, the structures are worked on year-round and include a design competition and engineering phase.

The most anticipated and eye-catching part of the fair, involving the Portada is the very beginning when the “alumbrao” occurs - that is, the initial illumination of the gate by the mayor.

Conclusion

Much like the gate that illuminates the fair, the Feria de Sevilla itself reflects and illuminates a living canvas of Andalusian culture and identity. From its simple beginnings as a cattle market to its transformation into a showcase of the region's traditions, each caseta, lantern, and gate contributes to an atmosphere that only the energy and beauty of Seville can provide.

Sources

1 - Los pintores que fijaron la imagen de la Feria de Sevilla

2 - SEVILLA - Recinto Ferial - (Feria de Abril 2013)

3 - Hermandades en el Real de la Feria

4 - Cómo se decoran las casetas de la Feria de Abril de Sevilla

5 - Las casetas privadas, fruto del elitismo del Duque de Montpensier

6 - ¿Quién inventó los farolillos de la Feria?

7 - Portadas de la Feria de Abril