When one speaks of the French language today, there is no doubt as to which language it is, but this wasn’t always so. At what point does one of many languages, spoken by any one of many groups living in France, win out and become French? The fact of the matter is that France is not, and has never been, monolingual but what about the concept of French being a single language?

If the historical layers of standard French are peeled back, we find langues d’oïl, that is, a set of northern languages in a dialect chain (mutually intelligible languages in the same geographic region). The other main chain is found in the south of the country, and known as langues d’oc, or Occitan. Both chains together, as used in Gaul (modern day France), make up what’s now called Vulgar Latin.

The two language groups got their respective names from the way they said a simple word - “yes”. In the North, they said oïl (which later became “oui”) and in the South they said oc.

Vulgar Latin didn’t develop evenly in Gaul, since the South was colonized by Romans earlier than the North, making Occitan languages more romanized than Oïl languages. The former not only sounded more like Latin, it also took on less foreign influences, namely from the Germanic invasions in the North.

Over the centuries, Modern French would eventually develop from a subset of Oïl dialects spoken in the northern center of royal power - Orleans, Touraine and Île-de-France. The larger set of Oïl languages, across the whole of the North, came to be treated as dialects of a single language (sometimes referred to as francien), considered to be the main dialect of Old and Middle French.

Middle French Overtakes Latin

One of the first legal measures to change the de-facto language of government affairs, from Latin to the “French maternal language”, was a bill called the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts, signed into law in 1539. Articles 110 and 111 of the law [1] sought to bring clarity to any document of legal importance, impose the primacy of French as an administrative language, as well as shorten procedure by removing often badly understood Latin terms. Both articles are in use today, making them the oldest French laws still in existence.

The Ordinance wasn’t entirely novel, as it was preceded by three other royal edicts surrounding the preferred - but not mandatory - use of French in courts and administration. Additionally, French was already the main language of the government, making most edicts and ordinances administrative in nature rather than being sweeping reforms.

The French Institutions

The 1600s was considered the “Great Century” of French cultural dominance in Europe. By 1635, at the request of the statesman Cardinal Richelieu, the French Academy was created as the premiere institution to guide and protect the European lingua franca - the French language. Italy served as the model with its own version, the Accademia della Crusca, which in addition to being the oldest language institute in the world, successfully helped solidify the Tuscan dialect as progenitor of the Italian language.

The French Academy not only has a role as arbiter, as it publishes an official dictionary, known as the Dictionnaire de l'Académie française, with the first edition being presented to King Louis XIV in the late 1600s. While the dictionary is meant to be considered an authority, each edition takes decades to compile and publish, leaving room for other, more modern dictionaries to take its place (ex. those by Larousse and Le Robert).

Later editions, in particular the third and fourth, were the most innovative as they underwent orthographic changes in roughly half the entries. In all other respects, French spelling has been rather fixed for most of its modern history, as mandated by the Academy.

Similarly undergoing few alterations - aside from disruption caused by the French Revolution - the Academy has operated uninterrupted. Most of its existence has been spent under the umbrella of the Institut de France, which houses four other art and science academies and currently manages around 1,000 foundations.

Reign of Terror

Linguistic protection comes in many forms. A Royalist French writer, Antoine de Rivarol, penned an 1784 essay titled On the Universality of the French Language, stating why French belonged, just under Latin, at the top of a linguistic hierarchy, and how it was perfect as a universal language. He exalted it for its structure and logic, perfect for philosophy (yet sadly, according to him, lacking in its musical applications). Rivarol, raised in the southern Languedoc region where the Occitan language was prevalent, even went so far as to state that - different from French - other languages derived from Latin were vulgarized and thus unworthy.

Several years later, in 1790, a member of French Parliament named François-Joseph Bouchette - known as the Defender of Regional Languages - essentially put an end to the Ordinance of Villers-Cotterêts by proposing to make all official decrees be published in both French and regional patois, or idioms. Most translations came out of Paris but regional offices were also created to facilitate the publication of new decrees.

A few years later, however, the endeavor was scrapped in light of its high costs and under the weight of political changes that were going on at the time, principally the French Revolution. As French identity was consolidated, the bourgeois viewed the local languages as problematic, stifling the spread of their ideas. By 1794, speaking anything other than the langue d’oïl - that is, the French language - was considered counterrevolutionary and even deemed la terreur linguistique, or linguistic terror.

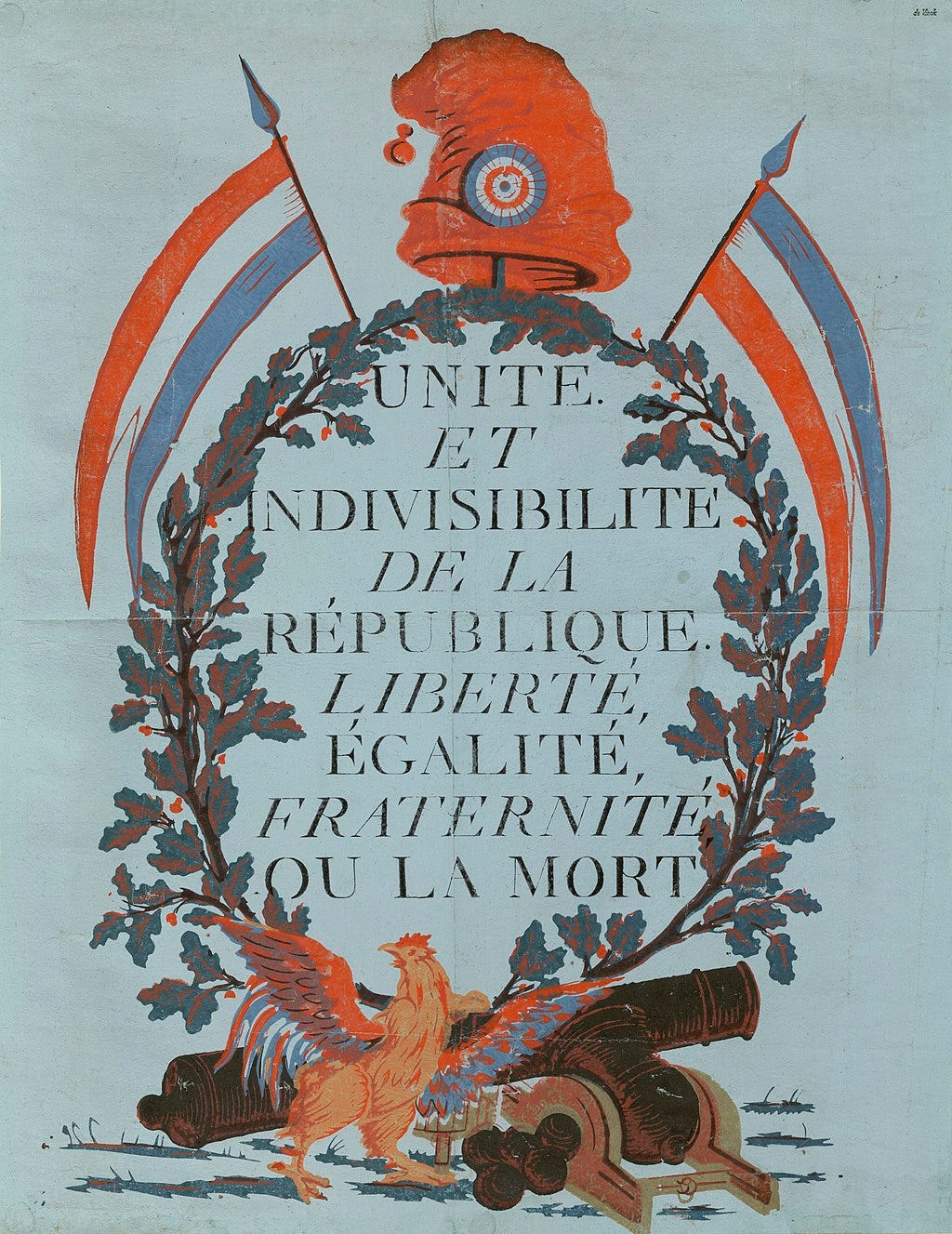

Language had effectively been placed under the charge of the State, and such Revolutionary slogans as a “united and indivisible Republic” and “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity (or death”, as another version of the phrase stated) could only be achieved if internal division was eliminated. On the one hand, equality was allowing everyone to speak their own language but, on the other, it was antidemocratic if the population at large was uneducated in the language of ideas and politics. For a dying kingdom in the throws of transformation, the ruling class saw reeducation as being more important than obscuratinism caused by an unaware majority.

Problematic for those wishing to force French upon society was the fact that French was only exclusively spoken in 15 of France’s 83 departments, according to a 1794 report by Abbé Grégoire. In populational terms, less than three million, out of 25 million countrymen (that is, 12%), spoke French in their daily lives. The “unimportant” patois were spoken by the masses.

Looking at another report - a census - 12 years later, the division of languages spoken appears, at first glance, quite different.

In the 1806 census, 58.5% speak a langue d’oïl dialect, 25% a langue d’oc dialect. The others are divided into Franco-Provençal, German, Breton, Corsican, Flemish, Catalan, Basque dialects. [3]

As mentioned previously, among the many Oïl dialects that the majority were speaking is one that is being deemed French, which seems to coincide with the 1794 report, at least in the sense that French was spoken by few.

A Matter of Education

Almost 100 years later, the Minister of Education Jules Ferry created educational reform with two laws, between 1881 and 1886, which made education compulsory and free for all children. It also made French the only language for all educational levels.

Before this point, due to teacher shortages in areas of the country that were isolated or far from the seat of government (and thus enforcement) - not to mention the lack of teaching material in French - schools had been able to teach in their regional languages and dialects. Knowing how to speak French was also rather useless to the parts of the population that had no reason to speak it in their daily lives.

Further developments would come in 1951, with the Deixonne law which finally recognized regional languages and introduced Basque, Breton, Catalan and Occitan into education. The years 1992 and 1994 saw the Constitution state that "the language of the Republic is French" and that the French language is "the language (...) of public services". While these statements gained constitutional power, similar points were already covered in much older laws, as previously mentioned.

Foreign Threats

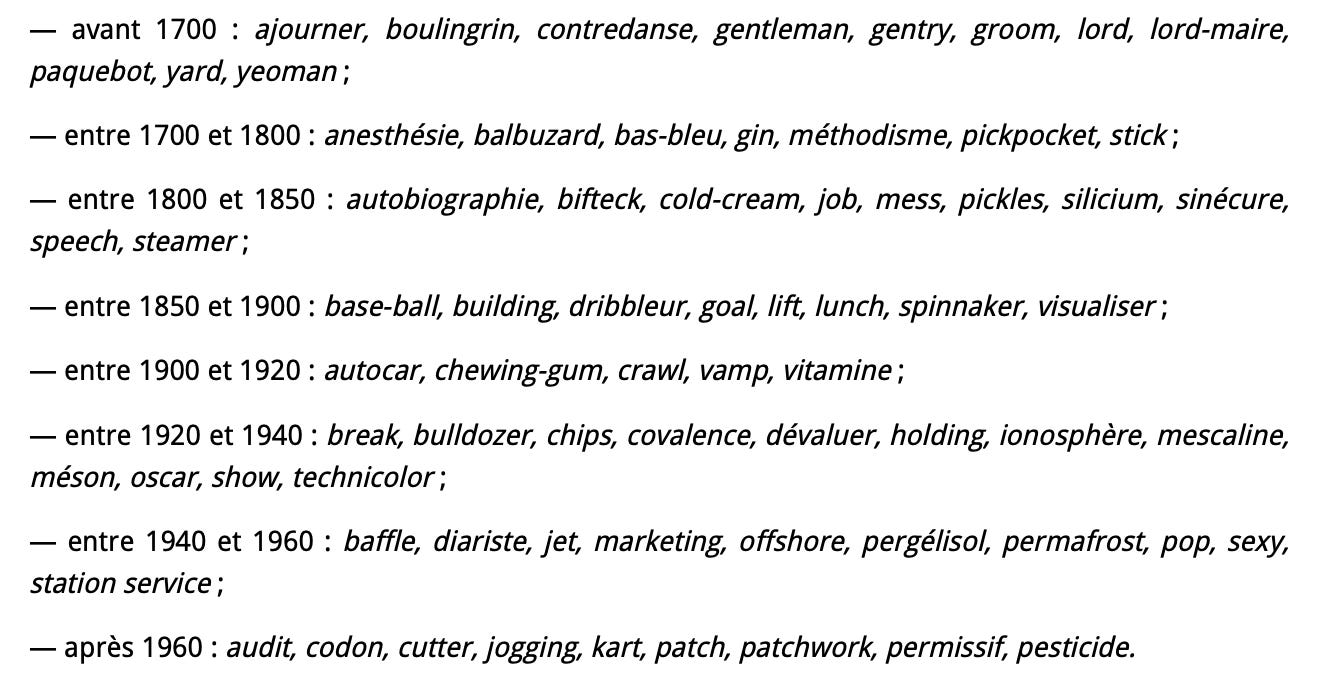

Threats to the French language are often seen as coming from outside the language, that is, from anglicisms. Borrowing terms from foreign languages has often been portrayed as a somewhat new phenomenon, principally due to American cultural supremacy, but it dates back centuries.

According to the French Academy, anglicisms in French belong to three categories: semantic, reintroductions and loan translations (ex. négocier, coach and guerre froide, respectively). Language purists reserve their ire for the worst offenders, namely words that have a perfectly acceptable option in the source language yet lose out to foreign (namely, English) vocabulary.

The possible confusion doesn’t end there. There are also psuedo-anglicisms, or borrowed words that are spelled like English words but have a completely different meaning in French (ex. spleen, which means melancholy, deriving from a proto-psychological theory that the feeling was related to the organ). Yet another example is the word sweat, meaning sweatshirt (additionally confusing due to it being pronounced “sweet”).

In the business and technology sector, anglicisms are more likely to crop up. In these instances, the Commission for the Enrichment of the French language came up with their own terms such as gazelle for a scaleable start-up, référencement naturel for search engine optimization, among many others [6].

Foreign borrowings come from other languages as well. Italianisms are actually more predominant in the French language than anglicisms, as a result of Italy’s own cultural supremacy during the Renaissance.

Of all the words of foreign origin listed in the Dictionary of the French Academy, English […] accounts for only 25.8% of imports, and is behind Italian, which leads with 27.42%. [7].

The French Academy, in its role as official guardian, is active in voicing its opinion when they see threats appear. One such case, in 2008, saw them come out against the government's proposal to constitutionally recognize and protect regional languages [8]. As recent as 2022, they opposed the rise of English words in everyday public and private organizations and firms.

The flagged terms include train operator SNCF’s low-cost Ouigo (pronounced “we go”) services, or imports from English such as “big data” or “drive-in” [9].

In regards to the 2008 skirmish, the government won and declared all the [regional] languages "are part of France's heritage", although a 2021 law which was ultimately vetoed shows there still remains work to be done in regards to lesser used languages [10]. Occitan even has a word for policies of linguistic discrimination: vergonha [11].

The English Doormat Academy, or Académie de la Carpette anglaise, which hands out awards to the French elite who overuse anglicisms, is a slightly humorous take on the matter (a list of past winners and each of their linguistic sins are here).

The Future is French?

Transgressions aside, French is well protected. Not only in regards to the institutions that preserve the language or, in some cases, that ridicule those who dilute it, but in the very real sense that all languages are alive and evolve over time. Changes are baked in. Out of nearly 40,000 words in the French Academy’s dictionary, a mere 1.76% are of English origin. Hardly an invasion.

According to a government report [12] written in 1999 by Bernard Cerquiglini, 75 regional or minority languages were identified in the country, including those being spoken in France’s overseas territories. Despite this finding, currently, around 94% of French people speak French, and it’s spoken as the official language in 29 other countries, many of which have populations that speak local languages, or what sociolinguists might call languages of low-prestige. Lingala, the second most spoken language in the Congo, is one such example, but it still loses out to French, with 51% of the country’s nearly 100 million population knowing how to speak it.

As a result of population growth, […] the number of French speakers will rise to over 700 million by 2050, 80% of whom will be in Africa [13].

The future of French is quite secure. It is not only one of the world’s top ten most influential languages, and among the five most spoken, it’s a language of prestige, international law and diplomacy. The French government plays a part in in it as well. President Macron promised to spend hundreds of millions of euros to increase the reach and influence of French around the world, in addition to announcing his intention to replace English as the predominant language in the EU and in Africa [14].

With the strengthening of French across the world and over the centuries, it created a vacuum that stripped regional languages of their legitimacy and growth potential. There’s an analogy to be made here, between the country’s urban centers and the so-called “French desert” - large swaths of the mainland suffering from low population density and divestment. Out of many regional languages, one was crowned French, but what policies and events led to most of the country being empty and few regions being deemed livable?

A subsequent article will investigate the problems inherent to favoring Paris over the provinces, and urban centers over low density regions.

Additional Information

1 - Histoire du français (in-depth timeline)

2 - Repères historiques sur la langue française (simplified timeline)

3 - Histoire de la langue française

Sources

1 - L'ordonnance de Villers-Cotterêts, Articles 110/111 (EN)

2 - Propaganda poster, 1793

3 - La République condamne les idiomes régionaux

4 - Dialects of France image

5 - Académie française: Questions de langue

6 - France Terme (French glossary for replacing foreign terms)

7 - Académie française: Questions de langue

8 - France's L'Académie Française upset by rule to recognise regional tongues

9 - Académie Française denounces rise of English words in public life

10 - The French government’s U-turn on regional languages

11 - Vergonha (Wikipedia)

12 - Les Langues de la France - Rapport de Bernard Cerquiglini

13 - The status of French in the world

14 - Macron launches drive to boost French language around world