Formal education arrived in Latin Europe via several routes and across countless centuries. It required the transformation of writing materials, the creation of centralized places of learning, the development of a succinct mode of literary production and even advancements in visual representations based on writing scripts. In short, it required systemization.

The backbone of any formal education system, aside from the knowledge that fuels it, is the recording medium for the collective and individual storage of information. Within any literary culture, from Mesopotamia to Europe, the act of writing, and thus reading, was transformed over time by the storage device. From clay tablets - upon which writing first developed - to papyrus, then parchment, each material provided improvements upon the last, culminating with paper.

From its Asian beginnings, paper migrated slowly, first to the Middle East and, from there, to Spain via the Moorish invasion. Meanwhile, printing techniques and knowledge followed suit, westward, evolving from an arduous task requiring excessive manual labor to a somewhat automated undertaking under European charge.

Paper manufacturing went through a mechanization process in Europe, with the inception of water-powered mills dating to 11th century Spain. The introduction of such technology - particularly with paper making advances spreading to the rest of the continent - greatly reduced the cost of production.

While the existence and advancement of materials used for recording information were integral to hierarchical and peer-to-peer knowledge transfer, centralized locations for the dissemination of said information were just as important. Formal education can be found in the earliest of civilizations, dating back to the first school systems in Sumer, while higher education can be traced back to the Egyptians, the Greeks and the Chinese, among others. However, universities as a concept got a unique start and were born much later, from religious instruction.

Cathedral Schools

The idea for the first Cathedral schools was created in 527 from the the tenets decided at a clergical assembly known as the Second Council of Toledo. In the few centuries that followed, these early schools could be found across Spain and Gaul (modern-day France). By the late 700s, Charlemagne issued his famous edict, continuing the tradition.

The Admonitio Generalis, issued in 789, was one of the most important legislative acts of Charlemagne's reign. It called for the opening of schools at cathedrals and monasteries and mapped out a general educational program for the future. Importantly, it emphasized the study of letters as the proper province of the clergy, prerequisite to understanding Scripture. Clergy were to assume an active role in the process of social reform. [2]

Cathedral schools, run by the Church, were originally created to educate and train new priests. They were centered around the libraries of European cathedrals and would eventually evolve into the earliest of medieval universities, especially as demand for education grew amongst the secular population.

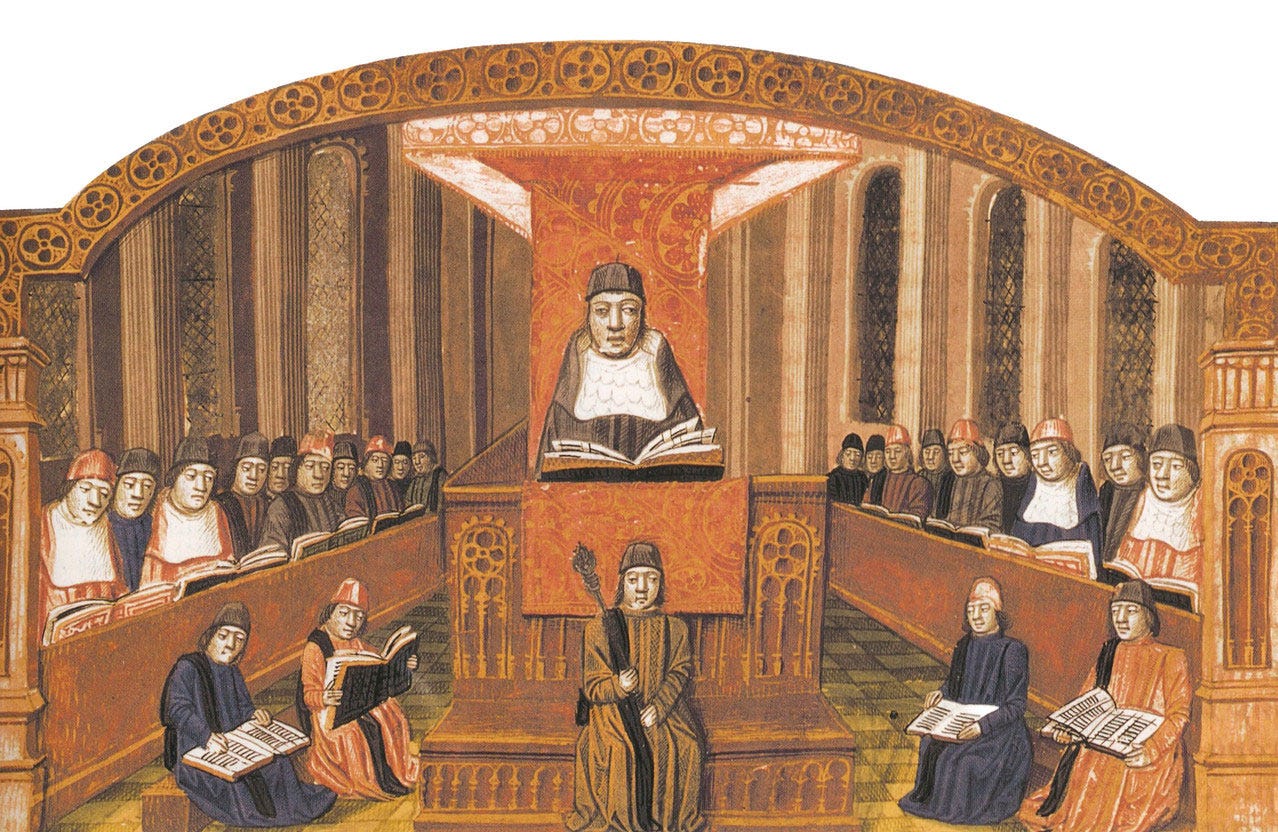

According to Carolingian precepts, the curriculum revolved around a specific set of core subjects going back to Ancient Greece. The trivium was the lower division courses made up of grammar, rhetoric and logic, which led to the quadrivium composed of music, arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy. These encompassed the seven classical arts under a liberal arts education, and were differentiated by the practical arts of medicine, law and theology. Offering these subjects were the earliest of the medieval universities, in Western Europe: Bologna (1088), Salamanca (1130), and Paris (1150). Rather than providing a general take on the subject at hand - such as in modern textbooks - the lecture texts of the era were often those of subject-matter experts, where students read Cicero for rhetoric, and Aristotle for logic. [4]

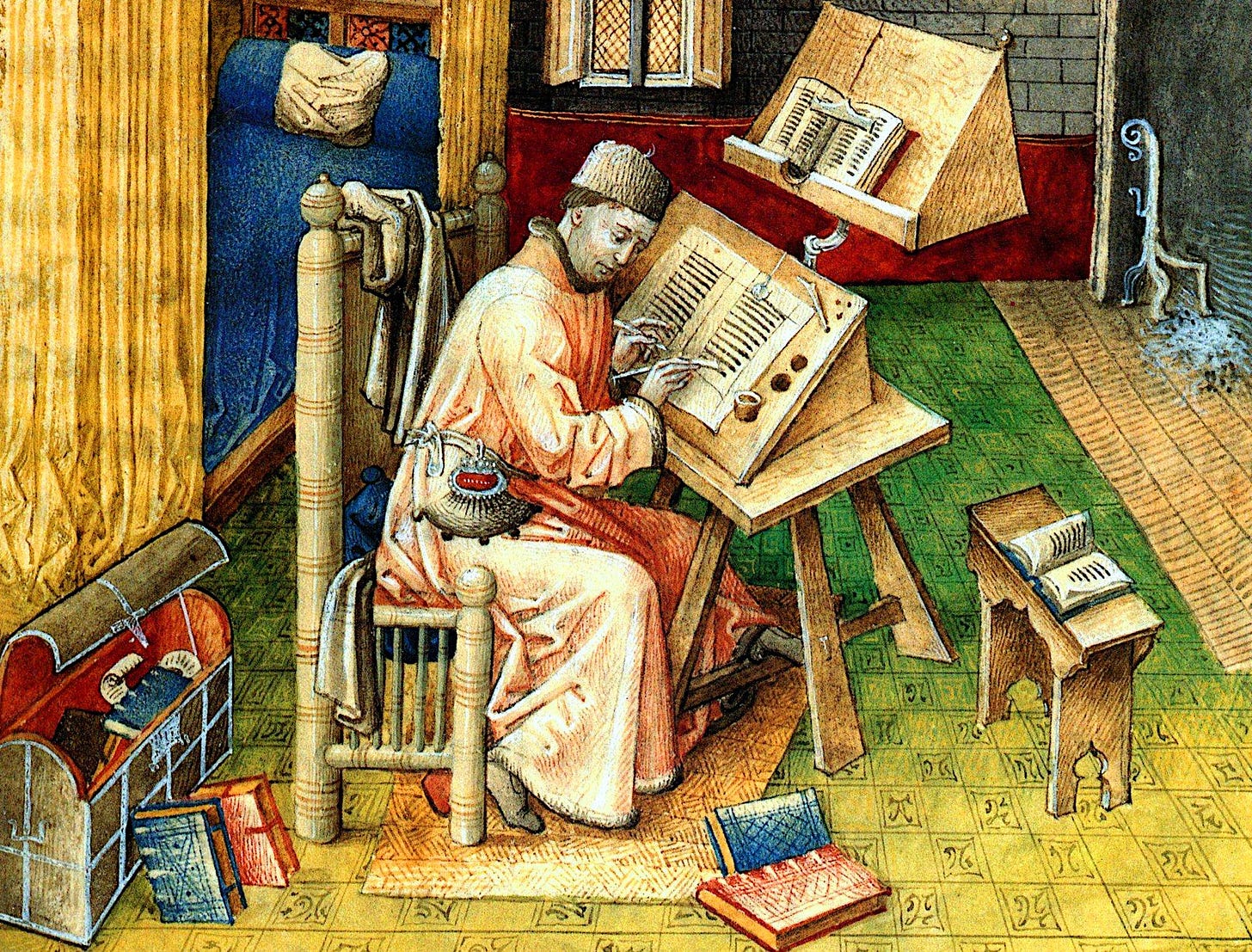

Cathedral schools continued to exist despite their evolution into studium generale, or the first universities, and for those who didn’t take the priest track, becoming a scribe was another option. These trained monks were involved in the entire codex-creation process, from sheet and ink making, to the careful and time-consuming process of copying texts, an affair that required anywhere from six months to more than a year’s dedication, from dawn til dusk, to reproduce a complete literary work.

The Pecia System

Over time, even scribal work was outsourced and thus altered course. Texts were created and copied less and less for religious reasons as commercial interests took over. The pecia system, created in the 13th century in a Dominican Convent, and popularized commercially in the 14th and 15th centuries, was essentially a handmade “photocopy machine” for the Late Middle Ages. In its religious context, it was like a novel but contained literary assembly line for making manuscripts, but commercially it was nothing short of a small revolution.

In the latter sense, the system started with the original version from the author - a subject area expert - and was followed by the creation of limited manuscript copies of that work - known as exemplars - at the behest of the author. An exemplar would make its way to the university library at which point it would be copied a second time, but in eight-page sections known as peciae, and these are owned by a stationer, who is often a university-approved rental agent and publisher. As a means of obtaining an exemplar, the university or stationer likely had a direct relationship with the author or the author’s representatives.

Finally, there were the end customers who, in most cases, would be students renting out one section at a time to either copy themselves or pay for a scribe to make them a copy [6]. Due to limited copies for any particular text, stationers did not have all sections available at the same time, much less able to rent them out in the order that the student required.

This system provided utility to other institutions as use cases grew in tandem with Europe's reading public. However, due to universities being at the center of literary culture, on account of the number of texts they started to hold in their libraries, an entire regulatory system emerged to control the accuracy of the copies and how they could be used. King Philip of France, for example, exempted universities from commercial taxes, which meant it was disadvantageous to do one’s literary dealings outside the higher learning institutions.

University administrators made themselves responsible for the exemplars which the stationers managed. The administrators, whether due to monetary recompense - since money exchanged hands at every step - or mere professional pride, created a verification process to make sure the copies were correct both grammatically and informationally.

The task of making copies would only become easier with the invention of Gutenberg’s moveable-type printing press in 1440, as well as the subsequent onset of printing towns, which were widespread throughout Europe. The main product of these initial printing towns was the earliest type of printed book, known as incunabula. They contained a general lack of standardization - that is, pagination, authorship, tables of contents, and the like, and were often stylized as manuscripts due to ease of recognition and familiarity.

The value perception between true manuscripts and the printed book was such that the “old-fashioned” manuscripts were later torn up and used as scraps to fortify early-modern book bindings for printed texts [7]. Changes in the production process were not limited to physical attributes but also by the script employed on the page.

Textual Aesthetics

The ability to share knowledge far and wide was aided by the unification and homogenization of vernacular lexicon, making literature easier and faster to print. Standardizing the look and characteristics of the written word helped to hasten the dissemination of scientific discoveries. This also meant that books were published even quicker which increased the copies available and allowed the average citizen to more easily access printed information with little to no travel required (an apt correlation to the modern information age is the ability to carry all the world’s knowledge in one’s pocket). In fact, literature could be carried on the body even in the Medieval period thanks to the invention of both pocketbooks and pouches attached to belts [8, 9].

Of course, literature wasn’t always easily accessible, from a physical or legibility standpoint. In the era prior to the fall of the Roman Empire, cumbersome scrolls were replaced by codices - the ancestor of the modern book - which made it possible to annotate and bookmark important sections.

Additionally, Latin would eventually become easier to read by dropping the use of scriptio continua, a writing style that saved room on costly paper by containing no spaces, punctuation and often all capital letters. Continuous script was based on capturing viva voce, or live speech, which was dictated to enslaved scribes, unintentionally leaving the resulting text open to varying degrees of interpretation.

Once the style fell into decline, the reader was no longer required to do mental gymnastics to comprehend the text and thus was able to take in the information at a faster pace, especially as the cost of paper decreased. Silent reading was also made possible by the decline in continuous script which doesn’t have an exact date of disuse.

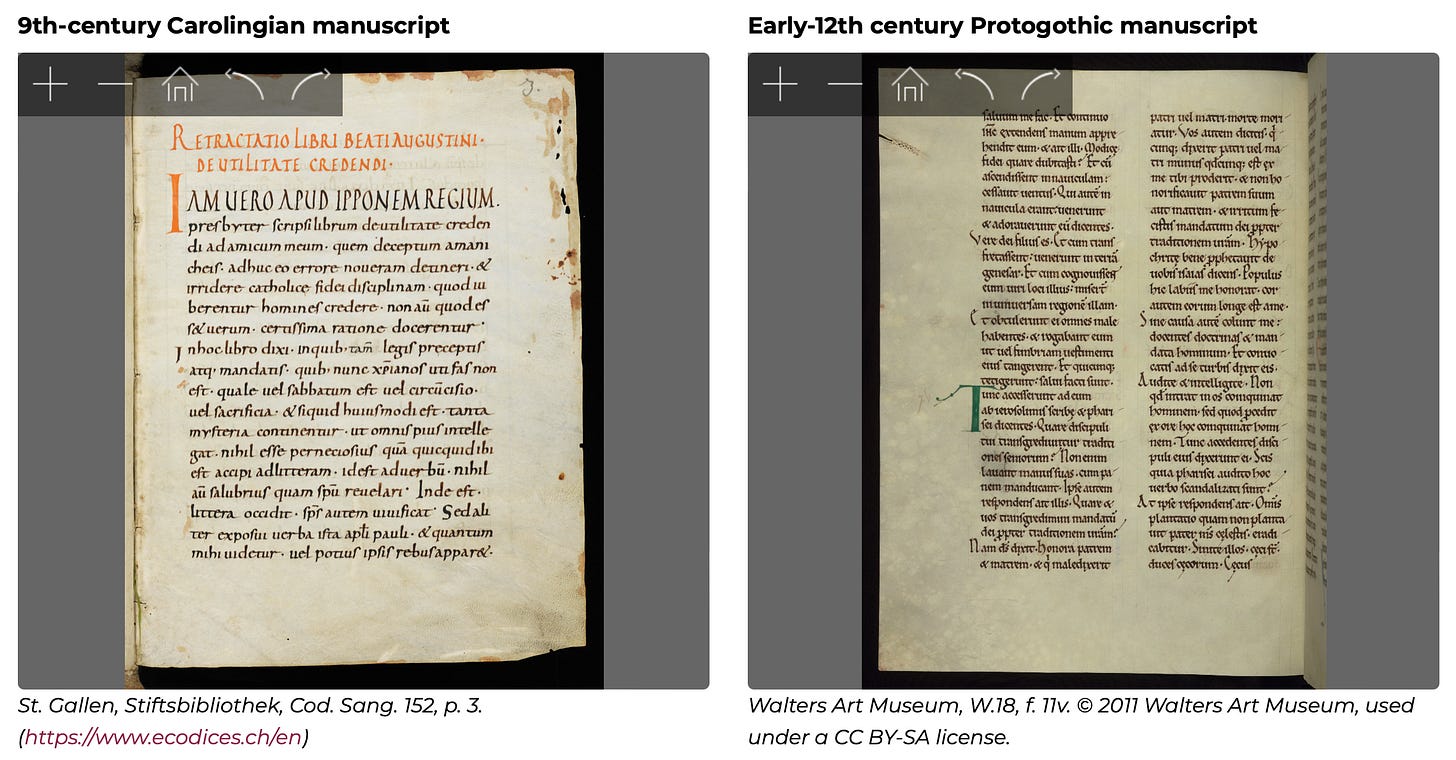

“Though paleographers disagree about the chronological decline of scriptio continua throughout the world, it is generally accepted that the addition of spaces first appeared in Irish and Anglo-Saxon Bibles and Gospels from the seventh and eighth centuries. Subsequently, an increasing number of European texts adopted conventional spacing, and within the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, all European texts were written with word separation.” [10]

Spacing and punctuation came to the wider reading audience, especially in vernacular Bibles used during sermons. However, an exception can be found in university texts which adopted a religious script called Textualis from the first half of the twelfth century. This particular script, essentially “gothic” in style, was dense and angular and allowed for more words per page under the pecia system.

Script changes and trends reflected more than mere aesthetics, as they were often utilitarian by design. Punctuation aided in the act of reading both silently and aloud, and in religious texts it served to preserve original meaning [12]. While not the first nor the last person to place spaces, periods and the like, on a pedestal, a debt is owed to Italian scholar Aldo Manuzio, who helped normalize the European use of punctuation in printed works through his publishing house in late 15th century Venice.

Knowledge Economy

It was people like Manuzio, among so many others, who brought incremental but important advances to knowledge sharing. One might deem it the original knowledge economy, which is a term that only originated in the late 1960s to explain the phenomenon of consumption and production based on intellectual capital. It’s considered most apt for the information age in which we now live, but perhaps it’s better suited to have arisen from the Renaissance period and the Age of Enlightenment that followed.

A learning society, where education can be undertaken regardless of location, could not have come about today without the innovations around parchment and paper, codices and books, cathedral schools and early universities, manuscript culture and the printing press, as well as the economy surrounding them - of paper mills, book binders, translators, ink producers, and others.

To some in the economy, involvement was simply an opportunity to make money but to others it was a chance to flame the fires of knowledge, whether teaching it, spreading it or merely illuminating its importance. There is often a negative connotation to the phrase, “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”, but some eras - such as the original knowledge economy - need to be remembered and, if possible, rejuvenated because they bring out the best of humanity.

Additional Information

1 - Latin Paleography: The different types of gothic

2 - Early Printing: Incunable, Uncunable, and Post-Incunabula

3 - Features of Latin New Testament Manuscripts

4 - Some Highlights of Education in Christian Spain the Late Medieval Period

5 - How Sumerian Civilization Gave us Our Present Schooling & Education System

6 - Space Between Words: The Origins of Silent Reading

Sources

1 - Jean Miélot (image)

2 - Charlemagne and kingship: the responsibility of absolute power (p. 44)

3 - Corso di teologia a Parigi (image)

4 - Lectures - Oxford

5 - The medieval scriptorium visualised

6 - The Pecia System and its Use in the Cultural Milieu of Paris (p. 24-25)

7 - Digitally leafing through invisible books

8 - Enchiridia (Wikipedia)

9 - Girdle books (Wikipedia)

10 - Scriptio continua: Decline (Wikipedia)

11 - Latin Scripts - Gothic Textualis

12 - The mysterious origins of punctuation

Thanks for reading Ambulatin! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.