Among the countless sententia, or popular moral sayings, that have historically existed, the adage that “Rome wasn’t built in a day” is oft-repeated. Originally mentioned in a 12th century Flemish court, it was popularized for early modern audiences in the 1500s, by playwright John Heywood in a book of proverbs. At the turn of the 20th century it was included in a book of medieval French poetry, Li Proverbe au Vilain, where one finds the following line, Rome ne fu[t] pas faite toute en un jour. The phrase in its spoken form possibly goes back much further, perhaps even centuries earlier to the very founding of Rome.

The building of Rome, at least from its origin to the height of the Roman Empire, was a process that lasted between nine and ten centuries. It starts with the legend of twin brothers, Romulus and Remus - raised by a she-wolf [pictured above] and a shepherd on the banks of the Tiber river - when they decided to build a city there [1]. A disagreement arose where Romulus killed his brother and named the new settlement Rome, after himself, and the reason why he did it speaks to the ancient beliefs in gods, ghosts and rites that shaped the city’s initial growth.

Pomerium, Augurs, Cippi

In the case of Rome, logic also played a part in the decision. The location along the Tiber river offered a natural trade route, and the easiest place to cross the river is where Tiber island - the only one along the river within the confines of the city - is located. But logic alone does not a city make.

Pre-Roman indigenous cultures such as the Etruscan, Latin and Italic peoples that inhabited the region didn’t simply found settlements based on geography. Rather, a set of intricate and detailed rituals, including divinations, had to be followed first. These rules weren’t limited to the location but also the geographical layout and urban planning of a new village.

One of the most important aspects to be determined beforehand was a consultation with the gods and a communion with the natural world, which was the work of the augur, or priest. The communion was centered around a practice known as taking the auspices, which meant the augur had to discern the meaning of bird signs including the direction they flew in, if they were alone or in formation, silent or making noises. Interpreting bird omens is a practice that both predates and transcends Rome.

Auspicia were dividied into two types, those requested by man and those that were doled out spontaneously by the gods. These were further divided into the different kinds of signs separated by type of event or animal, and complicated by a myriad of ways one could circumvent negative signs, such as through manipulating the interpretation or selectively framing the events.

Once a favorable location was found, a religious demarcation known as a pomerium was made in order to separate the sacred ground of the settlement from the rural Roman land, known as the ager romanus, or agro romano. The pomerium itself was made of two parallel lines, with a marked space in between for the trapping of malevolent forces that might negatively affect those inside the protected space. The boundary also meant that no weapons, except those carried by the emperor's guards, were allowed to enter the pomerium.

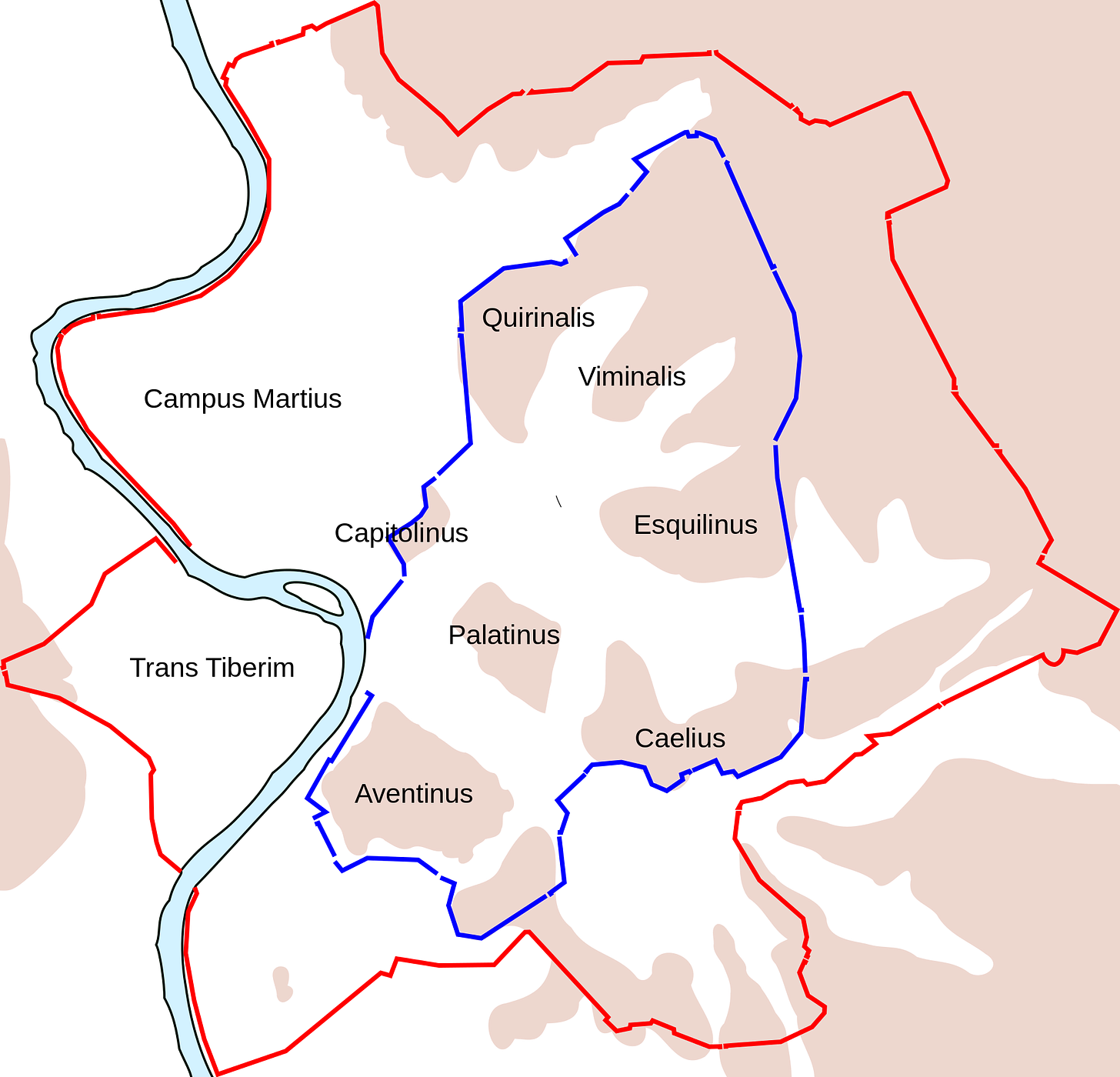

When Romulus and Remus were deciding on where to found the new settlement that would eventually become Rome, Romulus had a preferrence for Palatine Hill while his brother wanted it to be on Aventine Hill. According to the legend, this dispute led to Remus defiantely crossing the pomerium as Romulus was in the process of marking the outer bounds, with some versions saying that Remus was armed as he did it. The desecration of the sacred territory was sufficient that Romulus killed his brother and became the sole founder.

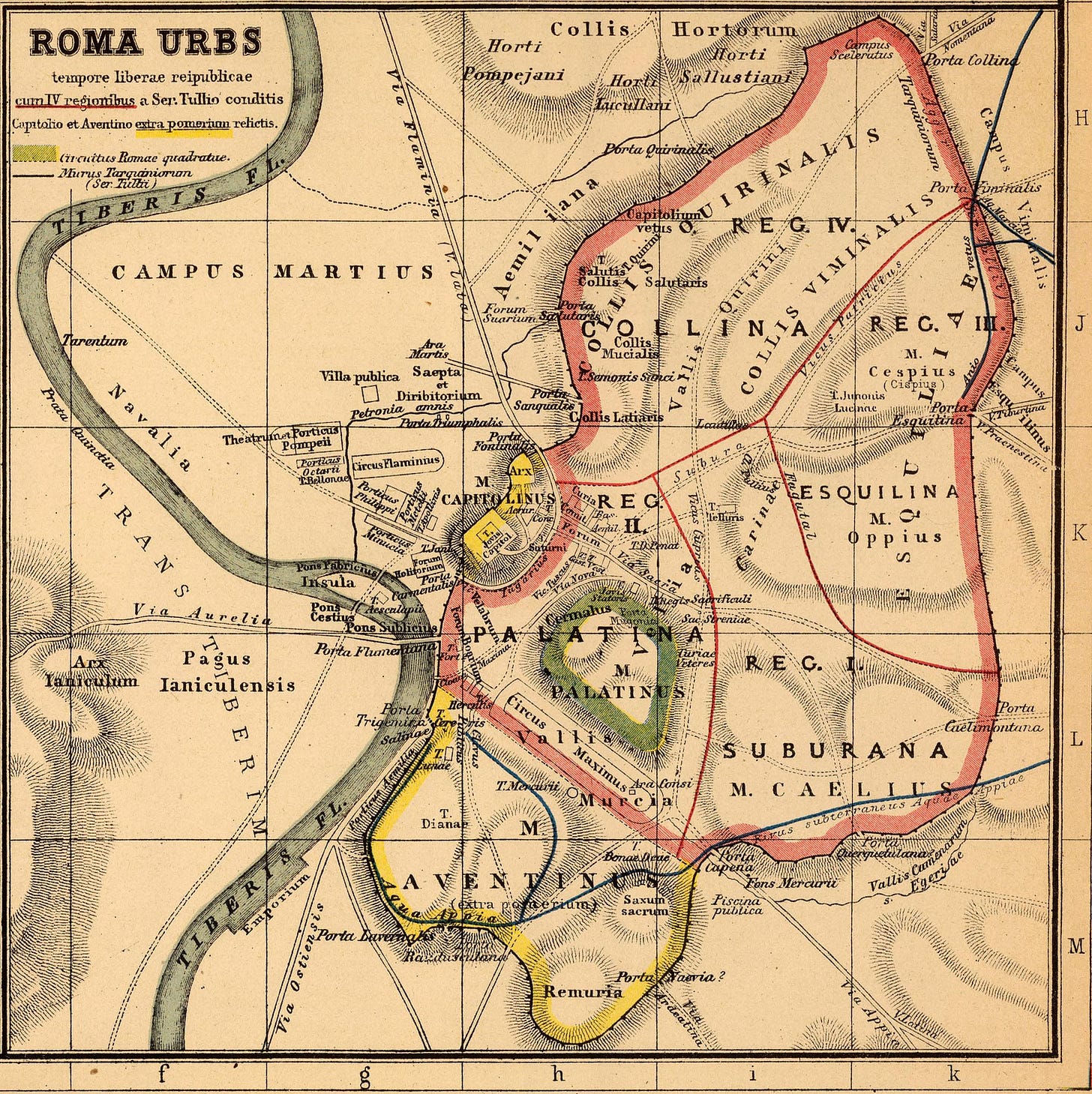

The boundaries of the original pomerium were reportedly deemed Roma quadrata, or squared Rome due to its rough outline, and only included the small area surrounding Palatine Hill. As the city grew over the centuries and military victories were had, the limits were marked by cippi, or marker stones. As Rome became more of a target by foreign military incursions, different Roman leaders erected fortified walls around the city that - while not replacing Rome’s religious boundaries - marked its practical limits.

The first of the two fortifications was the Servian Walls, built with volcanic rock in the 4th century BC, and which included the seven hills of Rome. As time passed, the city outgrew its boundaries, and the protection provided by field armies surrounding it lessened the need for the wall. Nearly four centuries later, the era of Pax Romana brought peace and stability to the region, further lessening the need. However, barbarian invasions - among other factors that were collectively known as the Crisis of the Third Century - brought about the end of the era and hastened the desire for new and improved fortifications, at which point the Aurelian Walls were built.

Gridiron layout

The arrangement of settlements also adhered to specific rituals. An umbilicus urbis, or navel of the city, was decided upon as a symbolic center that aided in calculating the geometries of the settlement or city. Next to it was placed a mundus, which was essentially a hole in the ground into which the initial inhabitants threw emblematic items representing daily life, as an offering to the spirits of their ancestors. The umbilicus and mundus gave birth to a new city.

From that point, the city’s expansion was mathematically divided in a gridiron layout by an initial crossroads known as the cardo (North to South commercial street) and the decumanus maximus (East to West street for general traffic of people and goods). An easy way of knowing where the crossroads of a Roman city is located is to find the forum as they were normally located near each other.

The overall urban design was based on a unit of measurement known as a “century”, and the total set of centuries was called a “centuration”. This type of grid - although widely employed throughout the Roman Empire - was not originally of Roman origin. It was borrowed from the Greeks, who surely borrowed it from other civilizations. One can find similar concepts at earlier times, in the Indus Valley, Ancient Egypt, Babylon, Ancient China and even Pre-Columbian America.

Road network

The Roman road network can be divided in two elements: the infrastructure and its use cases. The Via Consularis were the consular roads that radiated outward from Rome itself and extended to the far-reaching territories of the Empire. Somewhat similar to the decumanus maximus on the local level, it was built to facilitate the movement of people, goods and mail across vast regions. In short, it allowed for the constant flow of traffic and communications for administrative, commercial and military purposes.

While the Via Consularis provided the underlying network, another kind of network was operating on top of it. The Cursus Publicus was the Imperial Service that streamlined the movement and transfer of both government officials and vital correspondence. It was essentially a fast lane, but not in the sense of an exclusive expressway. What made it fast was its relay system of fresh horses and riders at intervals along each route - a system that was also employed in Ancient Persia and China. If all roads lead to Rome, the reason lies in these networks.

While not exactly a localized yet more modern version in any kind of comparative sense, the heart of contemporary Rome provides an example of how connectivity persists in the Eternal City today. Technically known as the A90, the Grande Raccordo Anulare (GRA) - which is simply called il Raccordo by locals - is a modern ring road and the most trafficked highway in the country.

Rooted in a 1878 law regarding the land reclamation of the agro romano, the decision to build it was taken in the 1940s post-war period (just prior to the country becoming a Republic) and the first section was inaugurated in 1951. As it stands, the GRA encircles Rome at a distance from the city center of about 11 km, covering 68 km of road with 33 exits at around every 2 km. Creating a road that encircles Rome wasn’t a novel idea, however.

Among the urban development plans for the city is the particularly important Master Plan of 1909 [4], which conceived of a city whose boundaries exceeded the Aurelian Walls. The plan included the creation of a ring road around the city which hypothetically would set the boundaries for the city’s urban growth. The idea was for the road to allow an alternative to traversing the historical center while facilitating access to the new outer neighborhoods.

During the Fascist government, the Master Plan for 1931 outlined a vision for the city as directed by Mussolini when he expressed the need "to create, adjacent to the ancient and the medieval...the monumental Rome of the twentieth century.” Part of that plan included an amplified ring road, and both Master Plans were precursors to the GRA. The period between 2003 and 2006 saw a new idea come to light, to be known as the Nuova Infrastruttura Anulare, which would have been an even larger ring road that would coexist with the GRA. Due to strong environmental protest, based on the fact that it would run through five conservation areas made up of parks and natural reserves, the NIA was never realized [5].

Rome today

Rome is unique in that it has the largest municipal boundaries in Europe, at 13 times that of Paris proper, making it difficult to plan for. The city’s latest Master Plan, from 2008, looks at making a “city of cities”, tying together the urban fabric with buildings, open spaces and enhancement areas [7]. It also aims to balance land use regulations with transport system design in order to preserve natural areas while easing traffic congestion (the latter of which was unsuccessful since Rome is still considered one of the world’s most congested cities).

The blame for the complexity of the city, though, can’t be laid at the feet of the federal government. Italy, though a unitary state, has land use regulations that align with federalist principles where each region possesses autonomy in shaping land use frameworks. Despite this, regions generally align with each other in their approaches.

The four levels of government - national, regional, provincial, and local - share planning responsibilities, with decisions predominantly at the local level, except for provincial restrictions like environmental impact laws [8]. A 1942 law, reflecting Mussolini's unitary administration, centralized planning and introduced zoning in urban environments, but a 1970 law allowed regions to have more autonomy. Further progress in the same direction was made with the 2001 constitutional referendum that decentralized governance, recognizing regional uniqueness.

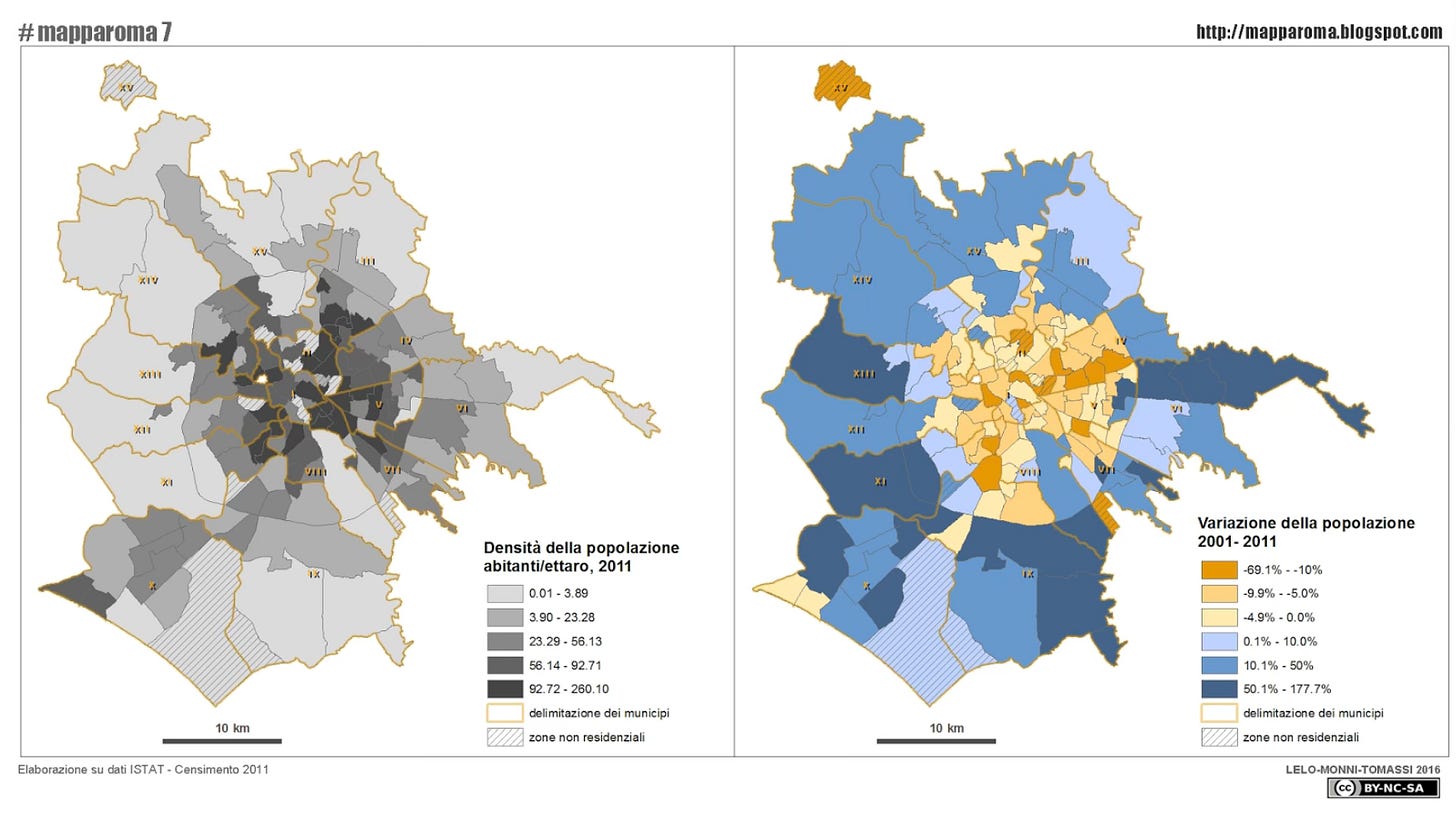

At 28 centuries, or 10.2 million days old, the city that “wasn’t built in a day” still continues to evolve, and not always in expected ways [9]. Between 2000 and 2022, the foreign population grew from six percent to nearly 14%, while the total population of the city - at 2.8 million - remains rather steady since the 1970s. That said, there is a trend of less births and an ageing population as well as the start of a demographic shift of women outnumbering men and single people outnumbering those who are married.

As for the future, Rome launched a Smart City initiative in 2021, compromising 81 projects which are already in progress [10]. The plan includes improvements in security, economic development, cultural participation, urban transformation, tourism, education and schools, social aspects, energy, environment, and mobility. Of course, “smart” merely means that all aspects of life will be tracked and traced, so the Latin phrase Qui bono? (who benefits?) is apropos in this instance.

With the growth of the city’s metro region - currently at over four million inhabitants - perhaps the natural evolution of the city is to be multipolar. Something along the lines of what Mussolini started with the EUR project, Rome’s first planned urban core outside the city center [11]. Formally known as the Esposizione Universale Roma, it was set to host the 1942 World’s Fair but was delayed by the large undertaking of draining the marshlands south of the city, and by the onset of WWII (which also led to the cancellation of the World’s Fair). Eventually, the EUR project was finished, but in a paired-down fashion compared to what it might have been.

For a multipolar Rome to work, the metro system would have to continue to expand outwards - though that doesn’t seem to be an issue - and, in the least, the problem of food deserts [12] would have to be resolved. Other main hurdles to be overcome are a lack of good governance, the slow pace of urban renewal, and a need for the recognition of Rome’s metropolitan status as a means of integrating planning and development strategies [13].

Should Rome aspire to retain its timeless legacy, Roma Capitale - the governing body that administers the city - will not only need a visionary at its head but a way to listen to the concerns of those that live there. With complex bureaucracies, of the type that Italians are used to, it’s a situation where there’s troppi galli nel pollaio (too many roosters in the chicken coop). And if one looks to the past as inspiration for how previous problems were solved, Romans might be better off finding some modern-day augurs to interpret bird signs.

If interested in how Paris came to be the capital, read my article here.

Additional Information

1 - Sacro GRA (documentary trailer)

Sources

1 - How was Rome founded? Not in a day, and not by twins

2 - Pomerium (Wikipedia)

3 - The Governance of Land Use in Italy

4 - Formazione della città industriale - XIX secolo

5 - L'ANAS vuole un secondo Raccordo Anulare

6 - Il centro si spopola, le periferie e l’hinterland crescono

7 - Il pgr ‘08 e il ruolo della storia

8 - EU division of powers - Italy

9 - Roma è una città che invecchia, ma gli stranieri ci salveranno

10 - Rome launches its plan to become a "smart city"

11 - 1942 World's Fair: Construction of E.U.R.

12 - Osservatorio Insicurezza e Povertà Alimentare

13 - La futura urbanistica di Roma: Alcuni temi