Cultured Kings and Knowledge Transfer

The expansion of Romance languages in Medieval Europe

Knowledge can’t be effectively spread without words, and words require a language. In some cases - such as the changeover from Vulgar Latin to fledgling Romance languages - the dissemination of knowledge is helped along by the spread of a new language.

The story of a language is really the story of the transfer of knowledge, which can occur in many different ways such as formal, informal, vertical or horizontal, among others [2]. The birth of Romance languages made use of all of these but the focus here will be mostly on the vertical, or rather hierarchial kind of learning, as opposed to the informal and horizontal kind.

Around the seventh century, written Latin began to fragment as documents showing regional differences started to crop up. This would have been a “natural” process (as much as the expansion of the Roman Empire could be considered natural) that occured as Latin spread across communities that had their own vernacular. Due to a lack of education among the common folk and the practical necessity of using a local dialect for everyday interaction, a diglossic environment developed.

This would be a long process, spanning several hundreds of years, as it wasn’t until the 10th century that these new Romance languages would begin to slowly take over from Latin in its written form. Depending on the country, the transition happened either by legal decree or via cultural propagation, such as with Portugal and Italy, respectively.

Examples of the transition

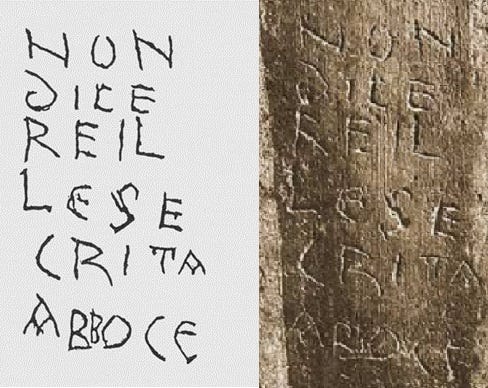

The earliest proof of a nascent Italian vernacular is evidenced by three separate events between the 8th and 10th centuries: the Commodilla catacomb inscription in Rome; the Placiti Cassinesi juridical documents in Campania; and the Veronese Riddle. In the 13th century, the Sicilian School of poetry greatly helped Vulgar Italian evolve and spread throughout the region and beyond, eventually inspiring subsequent generations of Tuscan writers. The father of Italian, Dante Alighieri, wrote a treatise - De vulgari eloquentia - praising the Sicilian School and the beauty of the vulgar language. Intellectuals debated the meaning of Dante’s writing, as well as the direction of a common language and whether it should follow the Florentine or Tuscan dialect (the latter won out).

Military occupation also played its part in the linguistic shift away from Latin. A prime example occurred from the eighth century when the Moorish invasion, and later conquest, of Iberia hindered the continued proliferation of Latin and thus aided its nascent offshoots. Another example is when a military force is otherwise occupied in a far away location (such as when the Romans fought the Persians), leaving an opening for foreign armies to invade and thereby influence the language of the invaded population. In fact, it was the preoccupation with Persia that allowed the Arabs to invade Iberia.

In France, there was an example of Latin being corrupted in a more literal manner, with badly translated or copied texts. In Charlemange’s Epistola de litteris colendis, a letter to Abbot Baugulf of Fulda which promoted his ideas on educational reform, the Emperor writes:

[…'] the wisdom for understanding the Holy Scriptures might be much less than it rightly ought to be. And we all know well that, although errors of speech are dangerous, far more dangerous are errors of the understanding. [4]

Discouraged by the knowledge of a loss of understanding, Charlemange pushed to keep Classical Latin at the forefront in the 8th and 9th centuries. This revival was one of many aspects to be known as the Carolingian Renaissance, which “covered educational and ecclesiastical reform within the Frankish kingdom, [and] established his religious and educational aspirations for the kingdom”. [5]

However, Latin wasn’t legally imposed. In instances where the majority of parishoners fared better in the vernacular, the king had no qualms about relegating Latin to second place. In fact, at the king’s request, the Council of Tours was created in 813, in which the Church mandated that priests communicate to their parishoners in the vernacular - be it rustica romana lingua or Thiotisca (Vulgar Latin or Frankish, respectively).

Some consider the edict by the Council of Tours to mark the birth of the French language. Due to wars, the traditional province of Touraine, of which Tours was the capital, would become the seat of the French court from 1430 to 1530. The French spoken there was considered the purest in the kingdom. By 1539, King Francis I made French the official language of France.

The Reichenau Glossary - created to aid priests in updating, or better translating, Latin terms that fell into disuse - became indispensable for having a decipherable Bible. For more than a millennia, until the year 1530, the most widely-known Bible was the common-tongue Vulgate but it underwent many revisions over the centuries and thus required a separate glossary.

Highly prized in monastic culture, these glossaries often traveled great distances, and were collected and recopied into larger compilations which amount to forerunners to modern dictionaries. [6]

Spreading knowledge in the vernacular

Centuries after Charlemange’s rule, as the High Medieval Period came to a close, both Spain and Portugal had their own cultured kings. Alfonso the Wise, as the 13th-century Spanish ruler was unofficially known, espoused learning through exposure to the arts, an approach that was followed by King Denis in Portugal. Alfonso’s aim wasn’t just to intellectually enrich his court and the surrounding nobility but to bring Castile out of the Dark Ages, a task that wouldn’t be possible if learning required previous knowledge of Latin.

Alfonso was indispensible in promoting Castilian in courts, church and literature, as well as translating foreign texts into the vernacular. He wrote Galician-Portuguese poetry that was set to music, and sponsored a renewal of the astrological tables for better calculating celestial positions in relation to fixed stars.

Additionally, he supported historians in contextualizing Spain within world history, marking a significant intellectual advancement during his reign. One of the most important works in Old Spanish was the Estoria de España, a literary project that was spearheaded by the king in the latter half of the 13th century. The 790-page chronicle, told in four parts, details the extended history of the country and includes sources such as the Bible and chansons de geste, or medieval epic poetry.

Across the border, in Portugal, King Denis - who was the grandson of Alfonso - was also heavily into arts and culture, and went on to compose 137 cantigas, or lyrical poems, in the troubadour tradition. He also established the first Portuguese university in the 1290s.

European political theory of the time suggested that the kingdom is the body, the king is the head and heart, and the people are the limbs, thus everything works best when all are healthy. Such advice would be found in a literatary genre called mirrors for princes which were, for lack of a better term, “How to be a Ruler for Dummies”. In regards to the “limbs”, Alfonso’s efforts helped spread the sciences, literature and philosophy to the public, particularly in light of the Reconquest. His goal of spreading knowledge and producing an educated populace serendipidously lined up with the increasing ability to share that information.

The Holy Roman Emperor, King Frederick II of Sicily, who lived roughly around the time of Alfonso, spoke six languages and patronized the Sicilian School of poetry which itself was centered around his court. It was where the sonnet was born and where the Sicilian language was first attested to in its literary form.

Like King Denis, Frederick II also established one of the world’s oldest universities, in Naples. Additionally, he was a keen enthusiast of birds and their migratory patterns (though probably not in the auspicious sense). A great amount of the information and culture that the king surrounded himself with during his reign was collated from other cultures, such as the Greeks and Arabs. For those who didn’t have such unfettered access to any and all culture of the era, the drawing and redrawing of geopolitical frontiers - both linguistic and literal - forced cross-cultural exchange and learning. The borders between Portugal, Galicia and Spain provide ample examples.

Language borders

In the Northwest of Iberia, the linguistic separation was made evident, two years after the creation of the County of Portugal in 868 AD, when Galician-Portuguese, or Old Portuguese, was first attested to. The Portuguese Kingdom formed in 1139, but it wasn’t until the late 1200s that the Portuguese language separated from Galician.

Due to the Muslim conquest of Iberia which dominated the central and southern parts of the penninsula from 711 to 1492, Portuguese took on influences from the processes of Islamization and Arabization. According to the book Léxico Português de Origem Árabe, the Portuguese language suffered changes across 17 semantic fields and grammatical categories as a result of Arabisms [7].

In 1297, King Denis of Portugal declared that Portuguese - then simply called the “common language” - was to be used officially. Despite the regal sanctioning of the new language, nearly two and a half centuries would pass before the first book of grammar would be published in the Portuguese language, in 1536.

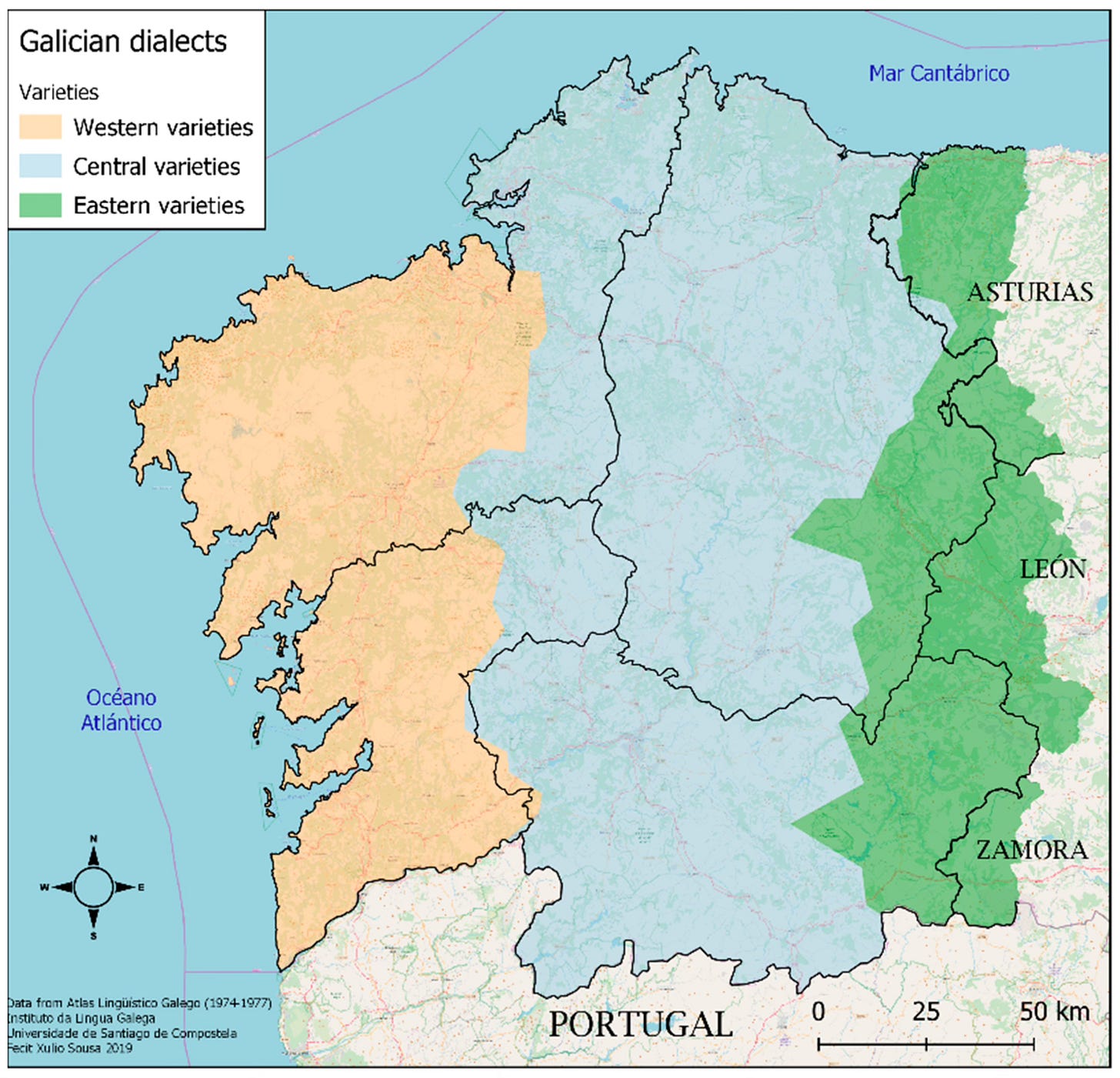

Galician, meanwhile, would adopt characteristics of the language of neighboring León and Asturias, a region that received less Muslim influence. In fact, there’s a well-known isogloss between the two regions where Galician and Asturleonese have produced spontaneous contact vernaculars [9].

While the strength and popularity of the Galician language ebbed and flowed over the centuries, Castilian Spanish rose to prominence. The earliest grammar book in the language, written in 1492 by Antonio de Nebrija, was the first of its kind for a modern European language and likely an early printed book. Nebrija is said to have dedicated it to Queen Isabella I, where he reminded her that:

“…language was always a companion of empire, and that it followed it in such a way that together they began, grew and flourished, and then together was the fall of both.” [10]

Many centuries later, an idea simliar to that of Nebrija would be popularized in New York and, subsequently, among linguists. That is, a language is essentially political while a dialect need not be, however the latter can become an impediment to the former’s consolidation. In essence, the influence of language on power dynamics and social cohesion is paramount.

Conclusion

As we look at linguistic evolution, the extent to which language boundaries were webs of power and influence is apparent, especially as Latin splintered into Romance languages. From medieval courts to military conquests, language has served both as a way to dominate and to resist.

Without the likes of Charlemange or the other cultured kings, Europe would have, in all probability, turned out very differently. An argument could be made for the positive effects of the printing press on wider society a few centuries later, but the population wouldn’t have been primed for such a development. These rulers laid the groundwork for later innovations that shaped European society, leading to a vibrant and dynamic intellectual and cultural landscape in subsequent centuries and for countless generations.

If you enjoyed this, you may enjoy its companion article.

Sources

1 - Image: Why is Charlemagne called the 'Father of Europe'?

2 - Knowledge transfer (Wikipedia)

3 - Image: Post from linguist Danny Bate on X

4 - Letter to Abbot Baugaulf of Fulda

5 - The Contributions of the Emperor Charlemagne and the Educator Alcuin to the Carolingian Renaissance

6 - Romance Languages: A Historical Introduction (p. 319)

7 - Léxico português de origem árabe: subsídios para os estudos de filologia

8 - Image: From Regional Dialects to the Standard: Measuring Linguistic Distance in Galician Varieties

9 - Atlas lingüístico ETLEN sobre la frontera entre el gallegoportugués y el astur-leonés en Asturias

10 - La lengua, compañera del imperio