It has long been said that there are two components at the heart of Catalan character: seny and rauxa. Seny is about rationality and common sense, while rauxa is about impulse and passion. Throughout Spanish history, the Catalan struggle for self-determination shows a lot of seny through the continuous political efforts to obtain autonomy, its commitment to preserving the region’s language and culture, and its sustained status as a strong economy. Yet when faced with the repeated suppression of its traditions and its fight for sovereignty, the rauxa can boil over. This duality helps explain Catalonia's long-standing drive for freedom from outside pressures, a struggle that has shaped its ties to Spain and reflects centuries of shifting power.

From the Middle Ages, Catalonia stood as a semi-autonomous principality within the Crown of Aragon, its self-determination likely stemming from its strong merchant class, healthy economy, and political influence within the Crown. However, this autonomy gradually declined after Aragon united with Castile in the mid-1400s. By the early 18th century, during the War of Spanish Succession - a struggle between the Bourbons and Habsburgs over who would rule Spain - the triumphant Bourbons under Philip V enacted the Nueva Planta Decrees, punishing Catalonia for siding with the Habsburgs. As a result, Catalan laws, language, and institutions were abolished or suppressed, leading to a period known as the Decadència, or decadence. Catalonia’s fight to protect its identity against centralizing forces began here, and it’s a struggle that still plays out today in different ways.

During the Nueva Planta period, the suppression didn’t just affect Catalonia and it wasn’t just about politics - it was about wiping out regional ways of living. Two of the main elements the decrees abolished were the long-standing furs, or forums, which were laws and privileges made for the region, by the region. The institution charged with the furs was the Corts Catalans, or Catalan Courts, which made laws that even the king could not revoke. The decrees, in effect, created the concept of Spanish citizenship and, in doing so, revealed how closely Catalan identity was tied to its language, culture, and institutions. This set off centuries of movements whose aim was to restore and redefine Catalan identity in the modern world.

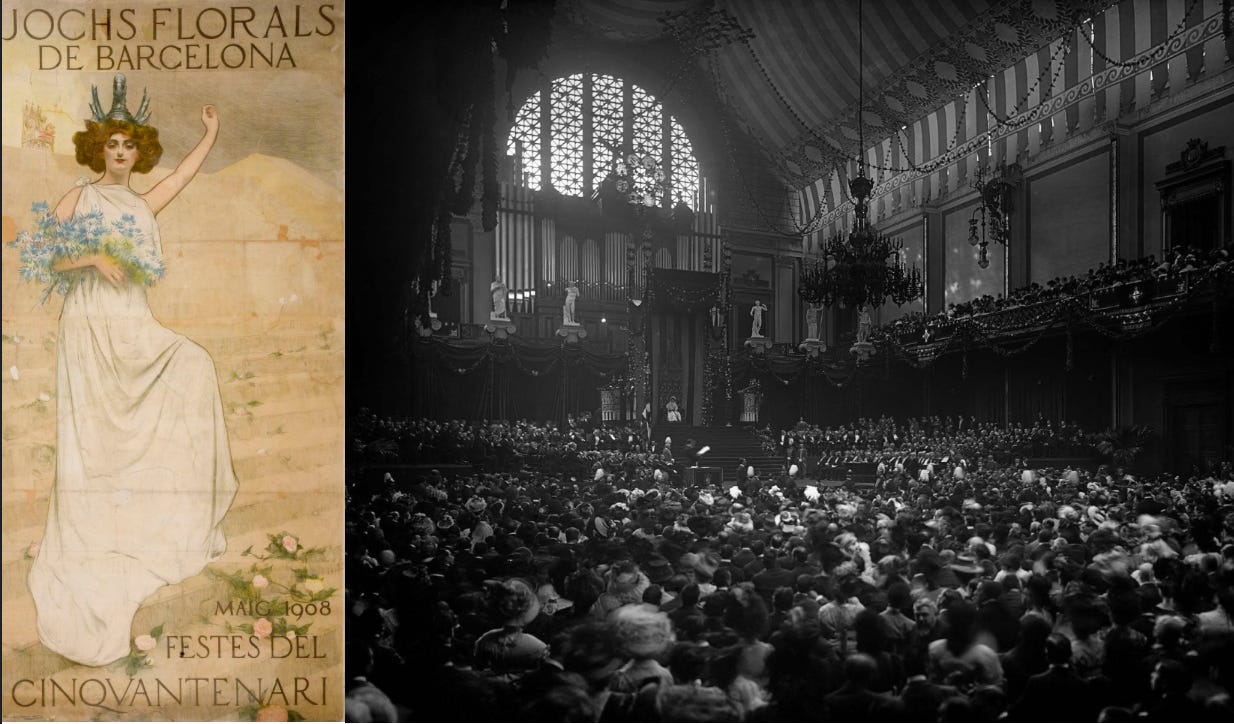

Spillover effects of the French Revolution together with the Cadiz Constitution of 1812, which recognized the importance of Spain’s regional languages and cultures, led to a more relaxed environment for the cultural revival of Catalan. From the 1830s, the Renaixença, or rennaisance, movement honored and highlighted Catalan literature, language and traditions. One of the recurring events that defined the period was the Jocs Florals (lit. Floral Games), a poetry festival from the 14th century that was given new life under the Renaixença. The revival strengthened Catalan pride and showed how culture can be a powerful political tool, a lesson that’s still a big part of Catalonia’s modern push for independence.

In the following passage, from Oda a la Pàtria by Bonaventura Carles Aribau, the author, who was living in Madrid, laments that he is far from his homeland and language. It was a moment that defined the start of the Renaixença.

Si quan me trobo sol, parl amb mon esperit,

If ever I find myself alone, I speak with my spirit,

En llemosí li parl, que llengua altra no sent,

In Lemosin I speak, for no other language is understood,

E ma boca llavors no sap mentir ni ment,

And my mouth then cannot lie or deceive,

Puix surten més raons del centre de mon pit.

Since more reasons come from the center of my chest.

(“llemosí” was a way of referring to archaic Catalan)

It wasn’t until the late 1800s and early 1900s that a more politicized movement relating to Catalan Nationalism started. It grew through a partnership between business leaders and cultural thinkers, combining pride in Catalan identity with the need to stay tied to Spain's markets. Business leaders were against independence because they relied on Spain economically. This created a balancing act between the type of nationalism that pushed for more autonomy but stopped short of wanting to break away from Spain. This era showed the practical side of seny, as Catalonia tried to balance cultural pride with the need for economic survival.

The effects of the Cuban War in 1898, however, can’t be overlooked [1]. As Spain came to grips with the loss of its conceptualization as an empire, following independence of both Cuba and Philippines, it led to a split nation and a crisis of identity. Those who believed vehemently in Spain as a nation-state were divided into two groups: the regenerationalists who sought reform and modernization, and authoritarians who wanted an even tighter unity and nationalism. Both groups opposed the idea of Catalan autonomy. The Civil War and the rise of Franco, which brought about a renewed suppression of Catalan identity, was a sign that the authoritarian strain won. This period showed Catalonia how important it was to preserve its culture as a form of resistance, and that idea would resurface more strongly under Franco.

With the end of Francoism and the creation of the Spanish Constitution of 1978, the country became more decentralized and, as a result, allowed for regional autonomy. This shift set the stage for significant social and economic changes. Among these was a growing trend of migration, both internal and from abroad, which would strongly impact Catalonia, culturally and linguistically. The move toward decentralization allowed Catalonia to take back some of its identity, but it also created challenges, such as finding a balance between fitting in and preserving what makes it unique.

Migration to Barcelona

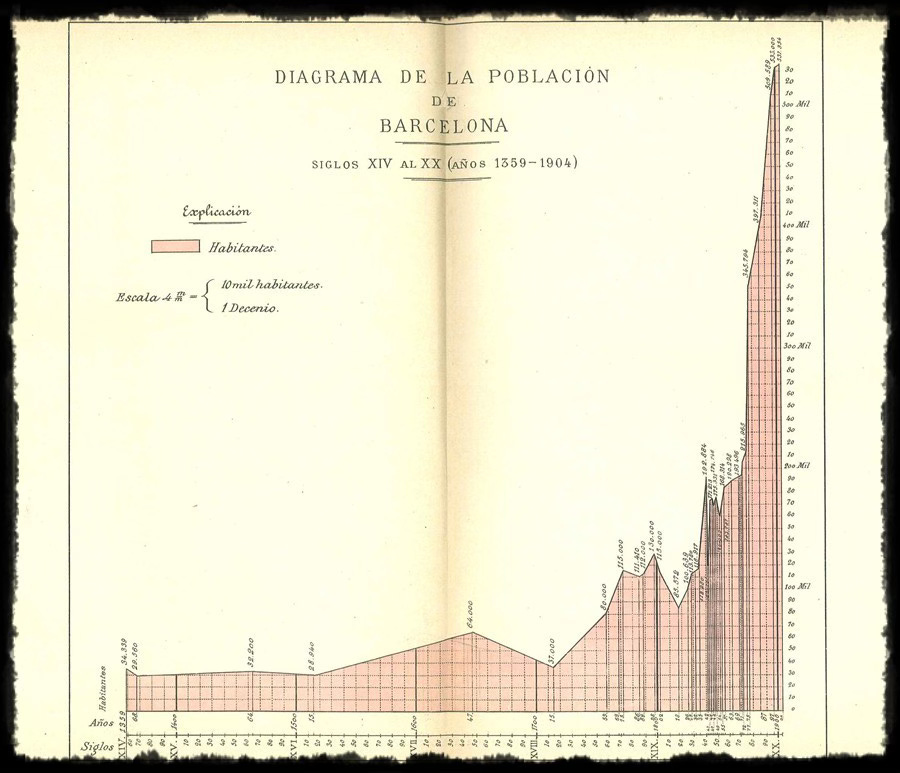

One of the stronger destabilizing factors in these changes is economic internal migration, particularly a shift from south to north and rural to urban, before nationals of other countries began migrating to the region. Between the 1830s and 1860s, the north of Spain started to industrialize, with Catalonia becoming known for its textiles and food manufacturing [3]. This process was aided by the expansion of Barcelona’s city limits following the demolition of its medieval walls in the 1850s, allowing for growth beyond the cramped and unsanitary conditions within the old city. Most internal migration before the Spanish Civil War actually came from within Catalonia itself, with a notable part of the rural population in the Barcelonès county moving to Barcelona for work.

The population of Barcelona doubled between 1900 and 1930, due principally to the arrival of migrants. […] Data provided by the population census show that the proportion of the population born outside the city of Barcelona, 40.8 percent in 1900, reached 56.1 percent in 1930. Municipal data available from 1900 onwards reveal that Barcelona received more than 400,000 in-migrants between that year and 1930 [3].

Regarding those who arrived from southern Spain,

Attitudes toward non-Catalan migrants hardened in the 1910s and 1920s. Growing migration from Murcia and Almeria involved large numbers of unskilled workers, who were easily recognizable by their Spanish (non-Catalan) language. In spite of these groups not being the most numerous among migrants, they attracted the majority of prejudices. Murcianos and Almerienses, in particular, were seen as lazy, irresponsible and difficult to integrate in the Catalan society and economy [3].

Despite the influx of migrants during the early 20th century, Barcelona managed the population growth, and within a generation, many newcomers were Catalanized [4]. The city expanded alongside industry during this period, but population growth slowed significantly due to the economic repercussions of the 1929 stock market crash, the Civil War, and the Second World War [5].

It wasn’t until the economic boom period known as the Spanish Miracle, of the 1960s and 70s, sparked another wave of internal migration. During this time, Catalonia became a magnet for rural Spaniards, particularly from Andalusia, attracted by job opportunities in the factories. Between 1950 and 1975, Catalonia took in nearly 1.5 million migrants, almost doubling its population. By 1975, 42% of residents in the province of Barcelona were born outside Catalonia [6]. This rapid influx made it hard for Catalonia to integrate all the newcomers. Many settled in the 20,000 shacks in the shantytowns like Can Valero on Montjuïc mountain and Somorrostro along the beach, creating segregated neighborhoods with a lack of facilities but a strong community [7].

As Spain recovered in the second half of the 20th century, migration patterns changed to include nationals from other countries, thereby straining the “onboarding” process that previously relied on ethnolinguistic similarities [3]. By 1981, the foreign-born population of Catalonia was just 1.5%, but by 2018, this number had risen to 18.2% [8]. As of early 2023, it stands at 17.2% [9]. While these numbers show significant demographic change, they don’t fully capture the cultural and linguistic impact on Catalonia. The arrival of international migrants further complicated the region's efforts to preserve its language and identity, as Spanish and other languages increasingly came to dominate public and private life.

As Catalonia welcomed a growing number of newcomers, particularly those who spoke Spanish or other languages, maintaining Catalan became increasingly more of a challenge.

Language

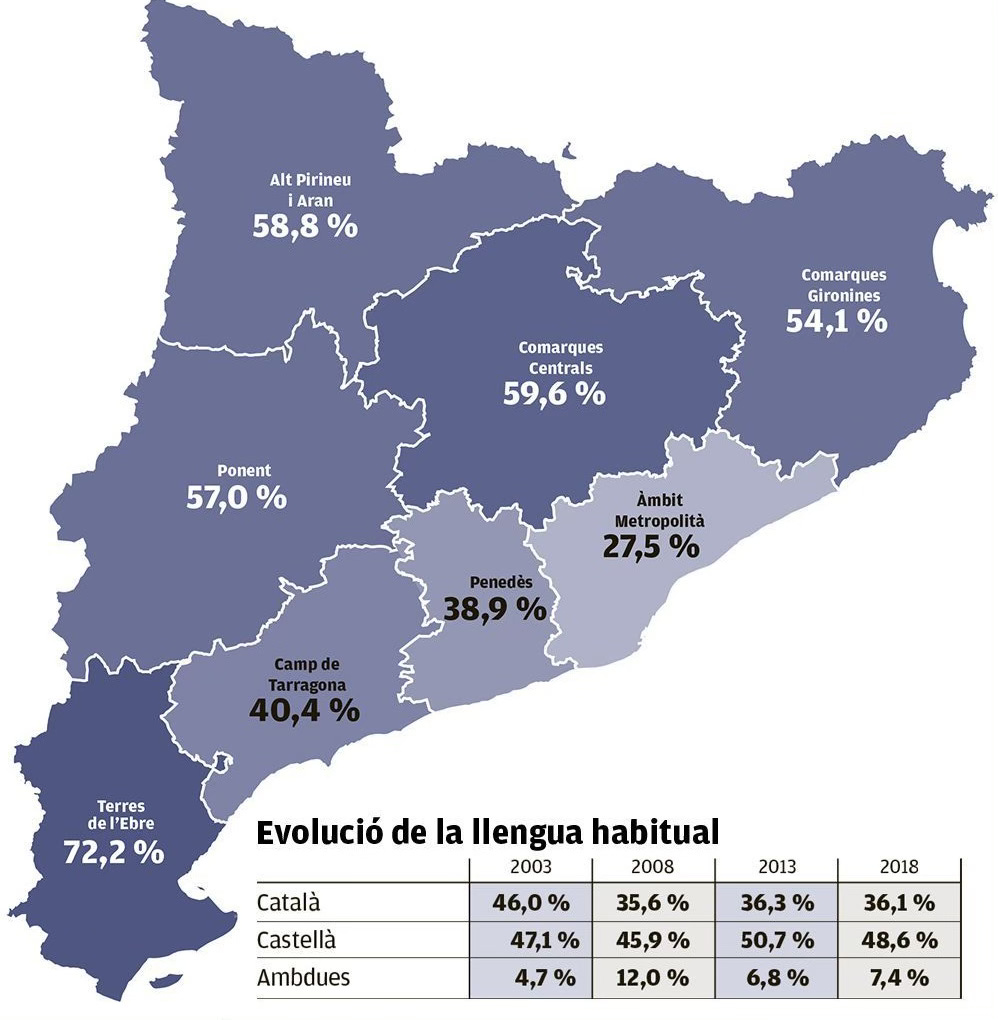

According to a 2018 study from the Catalan Institute of Statistics, 94% of residents in the autonomous region know Catalan and 81% how to speak it, while only 36% use it mostly as their everyday language [10]. This highlights an ongoing tension between authenticity and anonymity - between a language like Catalan, with a cultural gravitas, and one like Spanish, whose widespread use lends it a more neutral perspective [11].

In a 2024 GESOP poll, two-thirds of Catalan speakers said the language is less of an administrative or legal condition than it is a marker of a cultural or linguistic group [13]. In this sense, the importance of Catalan lies in its entanglement to regional identity, making a speaker of the language someone who embraces, engages with, and values the regional culture. This bond goes beyond personal identity, bleeding into the public sphere, as previously described.

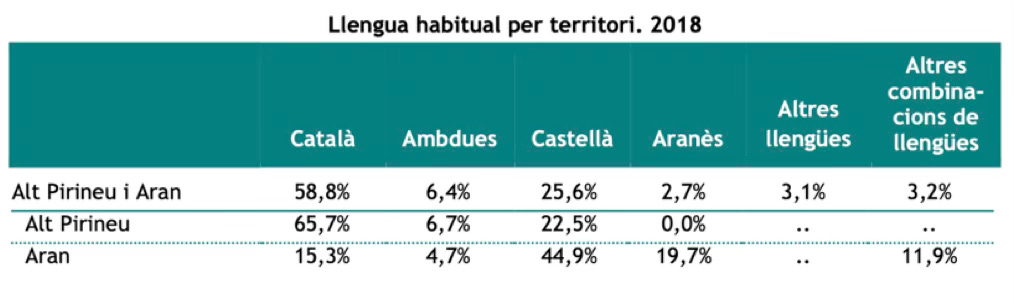

Before covering the geographical distribution of what people in Catalonia speak on a daily basis, it’s important to define a few terms. Within the autonomous community of Catalonia, there are regions called vegueries, like the highly-populated Àmbit Metropolità. These regions are further divided into counties called comarques, such as Barcelonès, which include cities like Barcelona. Two of the regions - Centrals and Gironines - are named after their main comarques.

The lighter coastal areas in the map above have some of the lowest uses of Catalan, and they happen to coincide with higher density populations, which tend to prefer Spanish in their daily lives. Not all is as it seems, though. At 58.8%, the Alt Pirineu i Aran region belies the disparity of Catalan usage, with the High Pyrenees showing 65.7% compared to the Aran Valley’s 15.3%. This is due to the latter’s special administrative status, its own language and its geographical isolation by the Pyrenees mountains. But even with Aranese being a bonafide language, Spanish is still 44.9% of the common use language there.

One of the ways that a language becomes common - aside from the ability to speak it - is whether or not conversations are initiated in that language. The official 2018 statistics show the following:

There are 1,507,800 people who always start conversations in Catalan and 1,716,800 who never do. Compared to 2013, there are 34,000 fewer people who say they always start conversations in Catalan and 133,800 fewer who say they never do. There is an increase of 230,000 people who say they often start conversations in Catalan. [10]

When clarified, the stats show that fewer people are consistently starting conversations in Catalan, but a larger number of people are now engaging with Catalan at least occasionally. Extrapolating out this trend, one might foresee a decline in Catalan use overall. At the same time, it might increase in formal or specific settings where the language goes from being something that’s alive and evolving to one that’s a cultural artifact, a language of administration, or simply a marker of resistence in cultural enclaves and counterpublics.

Protecting Catalan

In the 20th century, various laws have promoted or protected Catalan as a language, either directly or indirectly. The 1932 Statute of Autonomy first established Catalan as an official language, a status later suppressed under Franco's regime. Following Spain's transition to democracy, the 1978 Constitution set the stage for linguistic and cultural rights, leading to the 1979 Statute of Autonomy and the 1983 Charter of the Catalan Language, which established parity between Catalan and Spanish through the entire government [14]. These laws, among others, have collectively ensured Catalan's presence in institutions and the culture.

But with the constant, unchecked influx that results from irregular entries of third-country nationals, together with overtourism and Westerners living a borderless life, protected languages like Catalan are likely to come further under threat. With increasing globalization and internal migration, Instead of direct political conflict, Catalonia now has to find its way through more gradual challenges of migration and changing demographics.

Before passing away in 2023, the renowned linguist Carme Junyent said:

One thing that all threatened languages share is that no one is aware that they are threatened until there is nothing left to do. […] Catalan has all the typical symptoms of languages in danger of extinction. We are in a difficult situation, but not irreversible, and I think we can get out of it, but we need to start now [15].

In the face of these challenges, the survival of Catalan is not only the survival of a language but of a people’s identity. It’s a battle that, as history has shown, must be taken on with both seny and rauxa - rational thought and passionate resistance.

Additional Information

1 - El largo viaje hacia la ira (1969 documentary on internal migration to Barcelona)

2 - Barraquismo. Pasado, presente y ¿futuro?

3 - Perifèries Urbanes (images from Barcelona’s urban periphery, 1947-85)

4 - Els Jocs Florals de Barcelona (1859-2009): Un passeig per la història (pdf)

Sources

1 - La bilingüització de Catalunya durant el segle XX

2 - Anuario estadístico de Barcelona (1902-1917)

3 - The Labor Market Integration of Migrants: Barcelona, 1930

4 - Reversing language shift: theoretical and empirical foundations of assistance to threatened languages (p. 298)

5 - Evolución de la población, 1900-2002

6 - Change in National Identification: A study of the Catalan case (pg 19)

7 - Shantytowns in Barcelona: in the shadows of history

8 - Language Policy Report 2018, Govt of Catalonia

9 - Population and Housing Census. 2022-2023. Foreign population

10 - Els usos lingüístics de la població de Catalunya (PDF)

11 - Continuity and change: language ideologies of Catalan university students

12 - A Catalunya, dos de cada tres catalanoparlants consideren que la catalanitat és una identitat principalment lingüística o cultural

13 - El català té un problema que es diu 36 %

14 - Reversing Language Shift: Lessons from 3 Success Stories

15 - El català, en emergència